We use cookies

We use cookies to ensure that we give you the best experience on our website. Would you like to accept all cookies for this site?

Hoo Kwang, rectal prolapse

History

Hoo Kwang presented at the clinic with a 4-week history of tenesmus and rectal prolapse. She was free-roaming/stray, and had been brought in by her concerned caretaker. There were no other known health conditions, but she had not received preventive care such as vaccination and parasite control. Her caretaker fed her with commercial food and rice, and she was reported to have a good appetite.

Signalment

Age: 4-5 months (estimated)

Sex: Female Entire

Breed: Mixed

Weight: 4.2kg

Clinical signs

On examination, she was bright and alert, but showed some aggressive behaviour, due to lack of socialisation. Everted rectal tissue was present, consistent with a complete prolapse. This was examined carefully, and no necrotic tissue was found.

Incomplete prolapse mucosa only.

Complete prolapse all layers of the rectal wall in the entire circumference.

A well-lubricated finger was placed alongside the prolapsed tissue to distinguish between a prolapse and intussusception — in a rectal prolapse, the finger will not advance, and a fornix (blind end) is palpable. No other abnormalities were detected, and the patient had a normal hydration status.

Figure 1 — Hoo Kwang’s rectal prolapse. The syringe and needle are shown for scale.

Differential diagnoses

Rectal prolapse was diagnosed from clinical examination, but the underlying cause was not yet clear. Animals may be at risk of developing the issue alongside any condition which causes inflammation or irritation in the gastrointestinal, urinary or reproductive tracts, particularly those which cause tenesmus (1,2). Given Hoo Kwang’s young age, and lack of other clinical signs, a heavy parasite burden was a top differential for the underlying cause.

Diagnostic tests

Complete blood count and biochemistry were performed to determine the patient’s general health status and to investigate possible underlying causes of the prolapse. Her blood profile was within normal range, which allowed us to proceed with surgical treatment.

Treatment

Due to the chronicity of Hoo Kwang’s prolapse, treatment was colopexy and purse-string perianal suture, alongside ovariohysterectomy for population control. This was performed at the same time to avoid a repeat surgery.

Under general anaesthesia, saline solution was used to lavage the prolapsed tissue, to reduce gross contamination. Sugar was applied to reduce the swelling through hygroscopic action. This was followed by application of lubricant gel and manual reduction of the prolapsed tissue into the rectum. Finally, a loose, perianal purse-string suture was placed, using Supramid 2/0 (non-absorbable nylon monofilament).

Figure 2 — A purse-string suture pattern

Routine ovariohysterectomy was carried out via midline incision. Colopexy was performed to create a permanent adhesion between the descending colon and the abdominal wall, to prevent the prolapse recurring. A non-incisional, scarification technique was used, and sutured with PDS 4/0 (synthetic, absorbable monofilament). During the operation, metronidazole was administered at a dose of 10 mg/kg intravenously, over thirty minutes for prophylaxis.

After surgery, further medication was required:

Metronidazole: 25mg/kg BID PO for 7 days. Continued antibiotic therapy to ensure no post-operative infection occurred.

Meloxicam: 0.1mg/kg SID PO for 5 days. Analgesia, particularly for the discomfort associated with abdominal incision.

Lactulose: 2ml BID PO for 7 days. Laxative to ensure stool was comfortable and possible to pass through the purse-string suture.

During the operation, endoparasites were observed at the perianal area, and were identified as the most likely primary cause for the rectal prolapse. Therefore, anti-parasite treatment was also prescribed:

Pyrantel pamoate: 5 mg/kg given as a single dose, effective against roundworms (T.canis, T.leonina) and hookworms (A.caninum, U.stenocephala).

Post-operatively, an Elizabethan collar was used to prevent surgical wound interference. She was fed a low fibre diet to ensure faeces were of a soft consistency. It was important to monitor defecation to ensure she was able to pass faeces. External sutures were removed six days later.

Prognosis and case outcome

Prognosis for complete rectal prolapse requiring colopexy is good to guarded. Prognosis improves if there are no post-operative complications, such as infection or wound dehiscence, and providing the primary cause has been treated to prevent recurrence of the disease.

Hoo Kwang recovered well from the procedure. Her pain was assessed using pain scores and was well controlled. The team worked with her to improve her socialisation to make her stay less stressful. Her faeces were closely monitored, and she was able to pass soft stool during the first few days. The lactulose was discontinued when faecal consistency became liquid. Following this, she was kept under observation, and further intervention was required when she had a period of three days without passing faeces. Cisapride was prescribed (10mg PO SID for four days), two weeks after the original surgery. An enema was also performed with a small amount of saline (30-60ml mixed with KY gel). It was important to use gentle manipulation of the rectum to prevent recurrence of the prolapse.

Happily, following this treatment, Hoo Kwang continued to pass faeces comfortably and regularly, and was signed-off twenty days after her operation.

Figure 3

Discussion

Identifying the cause

Rectal prolapse is rarely a primary condition and is usually secondary to underlying disease. Successful treatment is reliant on identifying and treating the cause. It is therefore important to approach all cases of rectal prolapse with thorough history-taking and physical examination, as well as further diagnostic tests such as biochemistry and haematology, and imaging if necessary. Signalment can also help produce differential diagnoses, as younger animals are more likely to experience prolapse due to a heavy parasite burden and/or enteritis, whereas an older animal may be more likely to have underlying neoplasia or perineal hernias (1,2). In general, chronic straining to defecate (either due to passage of faeces, or due to irritation in rectum) can eventually lead to prolapse. This can become a vicious cycle, as the prolapsed tissue feels like material which needs to pass, and therefore straining continues.

Common underlying causes of rectal prolapse (1,2):

| Gastrointestinal | Urinary | Reproductive | Other |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Constipation

Diarrhoea Parasite infection Intestinal foreign bodies Neoplasia Perineal hernia |

Urinary tract infections

Urolithiasis |

Prostatic disease

Dystocia |

Congenital abnormalities

Physical factors such as anal laxity Any form of perianal/ perineal trauma (including recent surgery) |

Given Hoo Kwang’s age and history, endoparasitism was a top differential for an underlying cause behind the prolapse. She responded well to treatment, and it wasn’t necessary to carry out further investigations in this case. If the prolapse had recurred, urinalysis (dipstick, sediment examination, specific gravity), ultrasound or radiography would be considered as next steps, if available.

It is not always possible to identify an underlying cause, even with thorough investigation. In these cases, it is important to treat the prolapse and monitor closely for recurrence.

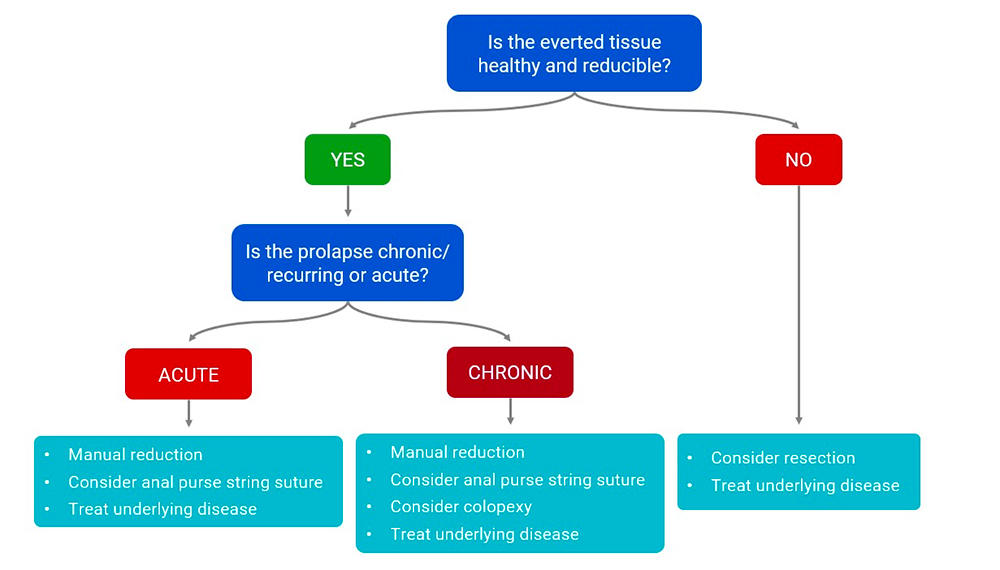

Deciding on a treatment

Rectal prolapse presents with varying degrees of severity and chronicity. The everted tissue can range from a few millimetres to several centimetres (as was seen in this case). The condition of the tissue can range from healthy and viable, to oedematous, and even excoriated and bleeding. Given the variety of presentations and the complexity of underlying causes, deciding on the appropriate treatment can be challenging.

Successful treatment requires evaluation of the whole clinical picture. As well as considering the primary disease, it is important to assess the nature of the prolapse. The following flow diagram is a suggested pathway to help guide decision-making, but ultimately it must be evaluated on the individual case.

Figure 4

It was surprising, in this case, that although the prolapse was large, chronic and complete, the tissue was still reducible and healthy. It was fortunate that there were no complications and resection was therefore not required. Even so, the prolapse had been ongoing for four weeks, with possible recurring episodes within that time, so it was felt that manual reduction alone would not be successful in preventing recurrence. Had she been left untreated for much longer, it is likely that the tissue would have become damaged and resection would have been considered.

Colopexy - does the method matter?

There are two methods commonly used for colopexy in canine patients. A non-incisional approach was used in this case as opposed to an incisional method. Incisional methods involve making a small, seromuscular incision on the surface of the colon and the abdominal wall, before suturing the incisions together. Both methods are well documented in surgical literature, and evidence suggests are likely to be equally effective (2,3). However, incisional methods may carry additional surgical challenge and risk of colon perforation. Therefore, non-incisional colopexies may be preferrable in resource-limited settings with fewer surgical facilities. The surgical procedure is considered successful if there is a good clinical outcome. Therefore, success also rests on the treatment of the whole animal, including addressing co-morbidities and effective post-operative care.

Minimising the risks peri- and post-operatively

Risk of infection — colorectal surgery carries a high risk of infection, due to possible contamination from the gastrointestinal tract. In this case, metronidazole was used prophylactically. Whilst preventive use of antibiotics is generally avoided in veterinary medicine (to prevent overuse), it was felt to be justified here and is often used during colorectal surgery for this reason (1). Contamination risk can be reduced further by making use of a non-sterile assistant during the operation, who can help with manipulation of the rectum/ anus as necessary, allowing the surgeon to maintain strict asepsis after entering the abdominal cavity.

Post-operative care — It is important that the patient can comfortably pass faeces after the operation, to prevent further straining and discomfort (and therefore reduce the risk of recurrence). The purse string suture should be wide enough to pass faeces easily, and placing a template (e.g. a small syringe) in the anal opening whilst placing the suture can help guide the surgeon. Stool softeners are useful to improve consistency and regularity, and these can be required for up to 2-3 weeks, or even longer, depending on the underlying cause of the prolapse. Deciding on an effective dose for medicines such as lactulose can be challenging and can vary by patient — as in this case, stool can become too liquid. Another difficulty in this case was managing Hoo Kwang’s constipation after withdrawal of lactulose. Fortunately, it was two weeks after the original surgery, so it was safe to consider an enema and use of cisapride, but otherwise a more gradual reduction in lactulose dose could have been used to prevent this.

Deciding when to remove the perianal sutures can also be difficult. This should only be attempted once the patient is passing faeces comfortably and regularly, and if no further tenesmus is present. This may be up to a week after the original surgery, but could be possible sooner. The animal should be monitored closely afterwards for recurrence of the prolapse. In Hoo Kwang’s case, monitoring her condition was further complicated by her habit of coprophagy; the nursing team had to be vigilant to ensure passage of stools was recorded, underlining the importance of attentive post-operative care in cases like Hoo Kwang’s.

Key points

- Successful treatment of rectal prolapse must include investigation of the primary cause.

- Evaluating chronicity, viability of the tissue, and degree of prolapse are important factors in choosing treatment.

- Attentive medical and nursing care in the post-operative period is key to a successful clinical outcome.

References

- ‘Rectal Prolapse’ in Fossum, T. W., ed. (2013). Small Animal Surgery. 4th ed. St. Louis, Elsevier Mosby. pp.577-580

- Popovitch, C.A., Holt, D., Bright, R., (1994) Colopexy as a treatment for rectal prolapse in dogs and cats: a retrospective study of 14 cases. Veterinary Surgery 23(2) 115-118 doi: 10.1111/j.1532-950x.1994.tb00455.x.

- ‘Colopexy’ in Fossum, T. W., ed. (2013). Small Animal Surgery. 4th ed. St. Louis, Elsevier Mosby. pp.536-537

About the author

Dr. Anupat Tanseree (aka “Dr. Earth”) graduated from Chiang Mai University in May 2018, and joined the WVS Thailand team the same year, working at our International Training Centre and shelter.

© WVS Academy 2026 - All rights reserved.