We use cookies

We use cookies to ensure that we give you the best experience on our website. Would you like to accept all cookies for this site?

Leah, Urolithiasis

Introduction

Here we describe a case of urolithiasis in a small-breed dog who was treated at the WVS International Training Centre in Thailand. Urolithiasis is a common urinary tract disorder of dogs and cats. In the case of Leah, she presented with haematuria and dysuria; through diagnostic imaging, we found multiple, large, triangular stones in her bladder and she was treated accordingly. Here is her story.

History

Leah was a stray dog that a local community member found wandering the streets near to the centre. It was suspected that she was once owned due to her familiarity and affection towards people. The local community members took Leah to a private clinic to treat her cystitis for 1 week; however, they could not afford the treatment cost and hence reached out to WVS Thailand for assistance.

Clinical signs

Leah was a female dog with an unknown sterilisation and vaccination history. She was given an afoxolaner-based flea and tick treatment (Nexguard®) from the private clinic in the previous week, but prior to that, she had no history of ecto- or endo-parasitic treatment. She had a friendly, relaxed demeanour and a good appetite.

Her clinical exam showed:

- Weight 5.15 kg, BCS 5/9

- Temperature 37.5°C

- Normal heart and lung sounds, pink mucous membranes, normal CRT, normal hydration

- No ocular or nasal discharge present, mild erythema across most of her body

- No abnormalities detected in musculoskeletal system

- Abdominal palpation elicited a mild painful response

- Haematuria with dysuria which occurred twice in the exam room (Figure 1)

Figure 1 — Leah's haematuria during daily walk

The community member who brought her in did not know how long she had had the abnormal clinical signs.

Differential diagnosis

Cystitis was diagnosed based on clinical signs but further diagnosis was required for the cause of the cystitis, such as infection, urolithiasis, tumour, abnormal anatomy, etc.

Diagnostic work up

CBC and Biochemistry

Complete blood count and biochemistry were performed to determine the patient's general health status. The blood results showed that Leah had a mild thrombocytopenia and mildly elevated urea and total protein levels.

Urinanalysis and Culture and Sensitivity

We also collected urine sample by cystocentesis for urinalysis, bacterial culture and antibiotic sensitivity test. The urinalysis result showed that she had protein and blood mixed in her urine but the sample did not culture any bacteria within 7 days; this allowed us to rule out bacterial cystitis.

Ultrasonography

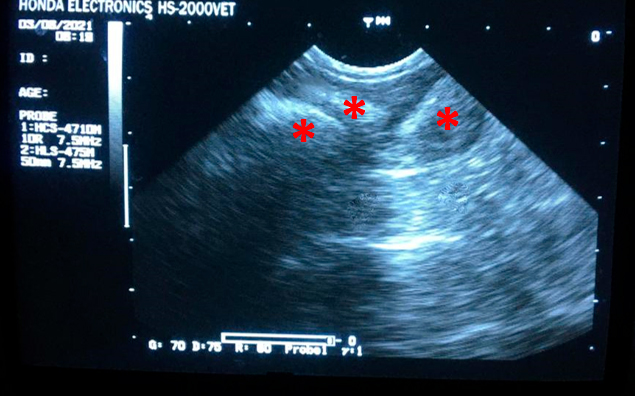

We performed ultrasonography, which revealed a thickened bladder wall and multiple, hyperechoic objects inside the bladder with acoustic shadows underneath (Figure 2).

Figure 2 — Ultrasound images of the bladder showing multiple, hyperechoic objects (stones, asterisks) with acoustic shadows underneath.

Radiography

Radiography showed that Leah had at least five, large, triangular-shape calculi in her urinary bladder (Figure 3).

Figure 3 — Right lateral abdominal radiograph showed multiple triangular-shape stones (dotted circle) in the urinary bladder.

Skin Cytology

Multiple cocci were found on skin cytology samples, but the skin scrapes did not reveal any ectoparasites.

Diagnosis

Cystic calculi and cystitis and a bacterial dermatitis.

Treatment

Leah had already been started on an amoxicillin and clavulanic acid (AMC) syrup at the veterinary clinic she had initially been taken to. We continued this course for a 21 day treatment.

- AMC syrup 20mg/kg BID PO for 21 days

Once we found cystic calculi in Leah's bladder through radiography and ultrasonography, we planned for surgical removal. Due to the size of these calculi, surgery was the only option available as they would have not been able to be passed or dissolved.

While waiting for the surgery date to be determined, we added NSAIDs to her drug regimen to reduce the inflammation and relieve her pain.

- Carprofen tablet doses 4.4 mg/kg, SID, PO for 3 days before surgery

Surgical technique: Cystotomy

After inducing the patient, a urinary catheter was placed to drain as much urine out of the bladder prior to surgery. This catheter stayed in place during surgery to reduce the likelihood of urine leakage when it was opened to remove the uroliths.

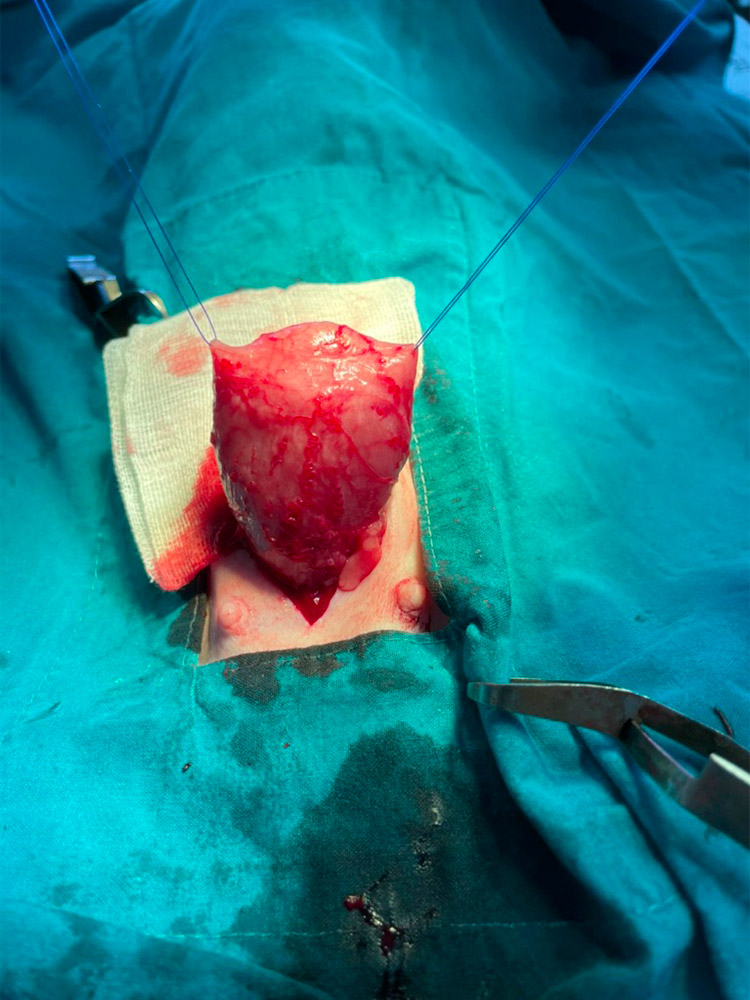

A caudal midline incision from the umbilicus to the pubis was made and the urinary bladder exposed. Two stay sutures (PDS 3/0) were placed on the lateral aspects of the bladder to maintain eversion and to facilitate manipulation (Figure 4).

Figure 4 — Stay suture placed in the urinary bladder

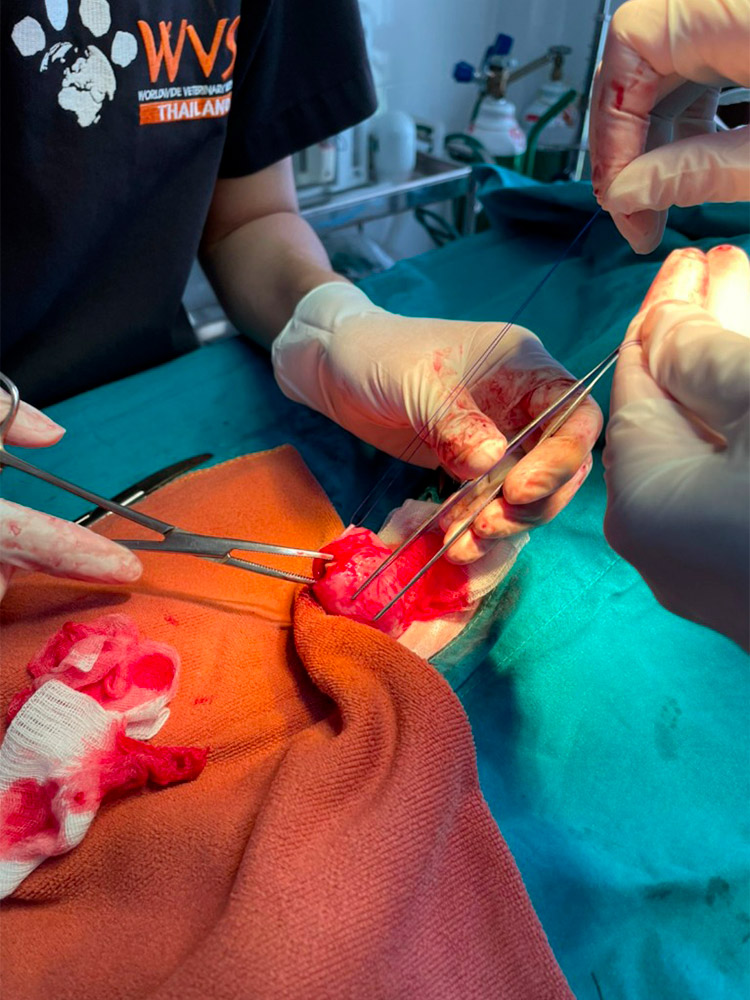

An incision was made on the dorsal aspect of the bladder. Rat-toothed forceps were used to grasp and remove the 5 triangular-shaped uroliths (Figure 5).

Figure 5 — Cystic calculi being removed via an incision on dorsal aspect of the bladder

One of the uroliths was sent for analysis. The bladder was then closed using an inverting Cushing pattern with PDS 3/0 (monofilament, absorbable suture) (Figure 6).

Figure 6 — Calculi removed and surgical incision closed

The integrity of the closure was assessed by injecting saline through the urinary catheter to distention. Fortunately, there was no leakage and so the stay sutures could be removed and the bladder could be replaced into the abdomen.

Lastly, the abdominal wall was closed using a simple continuous pattern with PGA 0 (multifilament, absorbable suture) in the muscle layer and subcutaneous tissue and continuous, intradermal sutures to close the skin with PGA 2/0 (multifilament, absorbable suture).

Post-operative care

Leah was observed closely after surgery for signs of complications, such as urinary obstruction or peritonitis. Fortunately, Leah could urinate normally in the evening after surgery without dysuria. If bladder atony had been present, the bladder would have been kept decompressed by urinary catheterisation or by manual expression once the bladder incision had healed.

Post-op medication used was:

- Carprofen tablet doses 4.4 mg/kg, SID, PO for 5 days

- Tramadol capsule doses 5 mg/kg, BID, Oral route for 5 days

- Continuation of the amoxycillin and clavulanic acid syrup doses 20 mg/kg, BID, oral route for 7 days

The surgical skin wound healed without any complications.

Prognosis

Prognosis for successful surgical treatment of urolithiasis without any complications can be determined as good to fair. But the recurrence rate for calculi formation may be as high as 12% to 25%. Recurrence is more common in dogs with cystine and urate stones than in those with phosphate stones. Appropriate medical management is necessary to decrease the recurrence of struvite calculi. So the long term prognosis would be dependent on the stone analysis result and preventive management. Unfortunately, in this case a definitive identification was not given with the sampled calculi being composed of calcium, phosphate, carbonate and urate.

Discussion

In Leah's case, at first we had to delay giving NSAIDs because she had been given a week's course of prednisolone from the private clinic and we didn't have her blood profile results yet. NSAIDs help relieve discomfort and improve urine outflow in cystitis cases. So, we aimed to start these as soon as the prednisolone had been excreted from Leah's system, and after we knew that she did not have significant kidney function problems (based on the blood test results) which would contraindicate NSAID provision.

There are two principal treatment strategies for treating urolithiasis in dogs: medical treatment and surgical treatment depending on the size and type of the stones. Hence, if possible, urinalysis should be performed to determine the type of stone present. Calcium oxalate, urate, cystine, and silicate stones cannot be dissolved and require surgical treatment. However, struvite stones can sometimes be dissolved by using a specialised diet.

Urolith analysis should be done to find the mineral composition in the stones, which will be very useful for prevention plan of recurrent urolithiasis. In Leah's case, we did send the sample but unfortunately the result came back as inconclusive. See below the table of Treatment and Prevention of Canine Urolithiasis below instead of discussion about preventive plan.

Table: Treatment and Prevention of Canine Urolithiasis

| Urolith type | Treatment options | Prevention |

|---|---|---|

| Struvite |

|

|

| Calcium oxalate |

|

|

| Urate |

|

|

| Silicate |

|

|

| Cystine |

|

|

*BUN = Blood urea nitrogen; PSS = portosystemic shunt

The main risk to the dog from uroliths are the potential to become stuck in the urethra and cause an urinary obstruction. A complete obstruction is a medical emergency. It is very painful and may result in damage or rupture of the urinary bladder. Urgent action is needed to relieve the pressure in the bladder; if it has rupture, an exploratory laparotomy must be performed to repair the bladder.

In most cases, clinicians will begin by attempting to place a urinary catheter. Once the obstruction is located, a syringe containing saline is attached to the other end of the catheter and the clinician will try to flush the urolith back into the bladder. If this is unsuccessful, a urethrostomy is likely to be required. In males prone to urolithiasis, performing a perineal urethrostomy can be very effective in reducing the distance potential uroliths have to travel by creating a urethral opening at the bend of the urethra in the perineum.

If uroliths are successfully pushed back into the bladder, surgery is likely to still be required to remove them as they are likely to become stuck again. Although, considerations should be made for animals who may be unstable under anaesthetic or recover from surgery poorly. If surgery is opted for, a cystotomy will be performed as described in this case.

References

- Fossum, T.W., (2013). Small Animal Surgery. 4th ed. St. Louis, Mo: Elsevier Mosby.

- Nelson, R.W. and Couto, C.G. Small Animal Internal Medicine (2014) 5th ed. St. Louis, Mo: Elsevier Mosby.

- Urinary Stones. American College of Veterinary Surgeons - ACVS. Available at:

https://www.acvs.org/small-animal/urinary-stones

[Accessed 30 August 2021]

About the author

Dr. Anupat Tanseree (aka "Dr. Earth") has been working with WVS Thailand since June 2018 after his graduation at Chiang Mai University (May 2018). Since then has been proved to be an enthusiastic and proactive young vet, quickly learning and proficiently training up to WVS protocols.

© WVS Academy 2025 - All rights reserved.