We use cookies

We use cookies to ensure that we give you the best experience on our website. Would you like to accept all cookies for this site?

Long: histiocytoma and splenomegaly

Introduction

Long was treated several times at our Thailand centre. He presented with multiple masses over the course of several months, and his treatment was complicated by a long absence from his community area.

History

Long was a free-roaming dog, who was brought to us by his caretaker, due to two lumps on the side of his chest. On palpation, one was highly mobile, whilst the other seemed more firmly attached to the underlying tissues. The consistency of both was very similar: round and firm. Overlying skin was normal. No other abnormalities were detected on examination, and he was otherwise healthy.

Initial investigation involved:

- Blood test: results all within normal range.

- Fine needle aspirate (FNA) from the mass for cytology

- Thoracic radiographs to check for metastasis: no masses found.

He was well in himself, so he was released back to his community area while we waited for the cytology result.

The result showed the masses were cutaneous histiocytoma. He was treated with prednisolone at an anti-inflammatory dosage (1mg/kg) for two weeks. His caretaker was phoned 10 days later, and he reported the masses were still the same size. An appointment for a second examination was booked, but the dog roamed out of his community area and his caretaker couldn’t find him for follow up.

He disappeared from his usual location for 15 weeks. When he returned, he had pronounced abdominal swelling and his caretaker brought him back to WVS for further investigation and treatment.

Signalment

Age: >5 years (estimated)

Sex: Male Neutered

Breed: Mixed

Weight: 19kg

Clinical Signs

When Long came back to the clinic, the original two masses were still present, in the same condition and size as before. On physical examination, he was quiet, alert and responsive. He had normal hydration with pink mucous membranes. Heart and lung auscultation were normal, and no peripheral lymph nodes were active. Abdominal swelling was noted as the main abnormality. Abdominal palpation suggested organomegaly or abdominal mass as possible causes.

Diagnostic tests and initial treatment

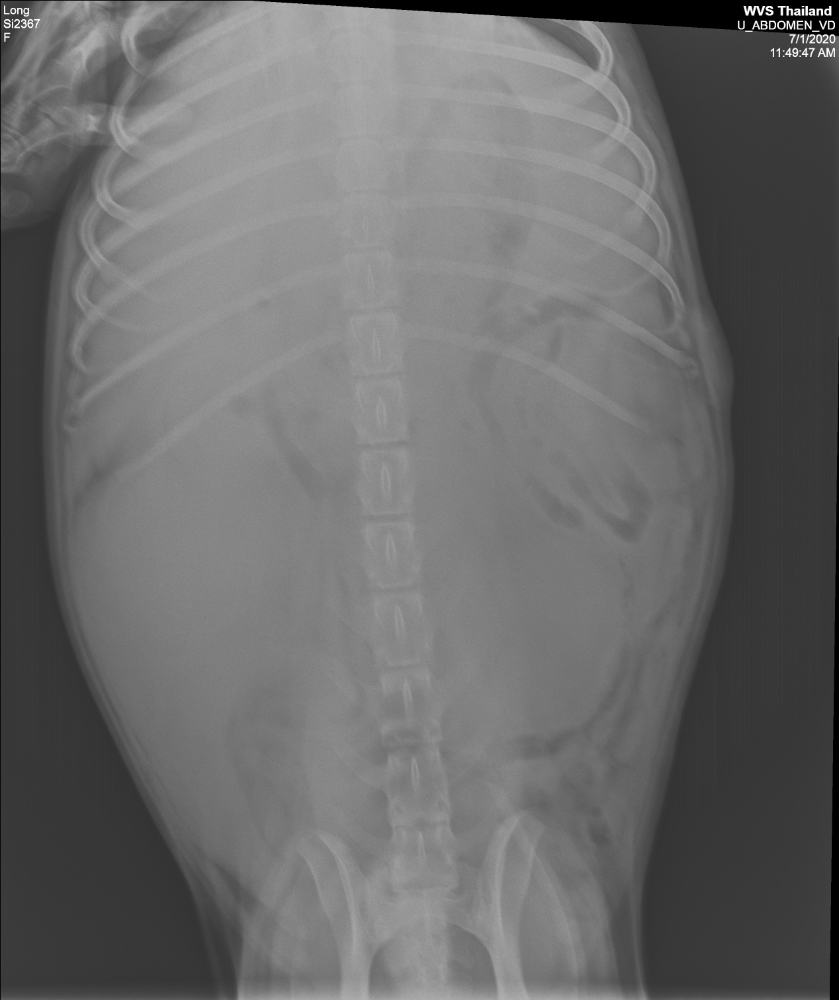

Long was admitted, and a blood sample was taken. Abdominal radiography was also performed, using three views (right and left lateral, and ventrodorsal). These showed splenomegaly (enlargement of the spleen). A splenic mass was highly suspected.

Figure 1 - Left lateral radiograph. Right lateral view was also taken.

Figure 2 - Ventrodorsal radiograph

His blood results were normal, so, an exploratory laparotomy was booked for the next day to further investigate the cause of abdominal swelling.

Exploratory laparotomy

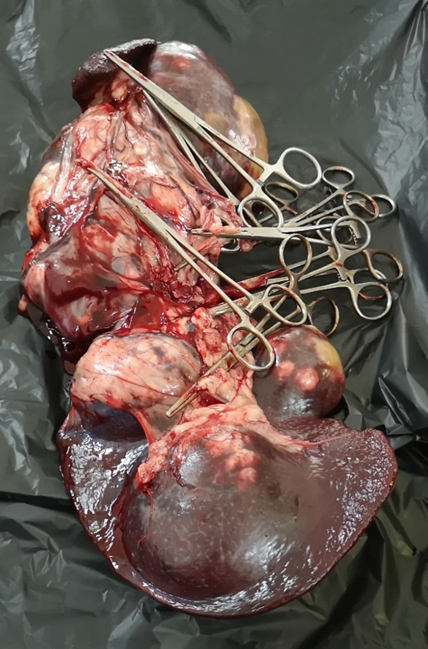

Diffuse multifocal nodules were found on the spleen with severe splenomegaly (weight 2.7 kg). None of the mesenteric lymph nodes seemed macroscopically active, and the liver presented a normal macroscopic appearance.

Figure 3 - Appearance of the spleen

Splenectomy

Total splenectomy was performed, and spleen biopsy was sent to be analysed at a pathology lab. The two original masses on the thorax were left in place, to avoid prolonging the anaesthesia.

Figure 4 - Spleen after removal.

Long recovered well after surgery. He received the following medication:

- Nexgard (afoxolaner) (10-25 kg) one tablet, given the day after surgery (and ongoing once monthly)

- Doxycycline (10mg/kg), PO, SID for 28 days

- Carprofen (2mg/kg) SID for 10 days

Tick control and doxycycline were provided to prevent Babesia infection, because patients are at higher risk after removal of the spleen (see Discussion). Carprofen was used for post-operative analgesia.

Differential diagnoses

There are various causes of splenomegaly or splenic mass, including those listed below (1):

| Neoplastic | Non-neoplastic |

|---|---|

| Haemangiosarcoma | Nodular hyperplasia |

| Haemangioma | Haematoma |

| Lymphoma | Thrombosis / infarction / congestion |

| Histiocytic sarcoma | Torsion |

| Mast cell tumour | Drug-induced e.g. barbiturates |

The biopsy result returned a suggested diagnosis of marginal zone lymphoma (MZL) based on the appearance of the sample. It was noted that MZL usually presents with associated lymph node involvement. Because lymph nodes appeared macroscopically normal, a differential diagnosis of nodular hyperplasia was also included. To confirm MZL, further testing using immunohistochemistry was required, which wasn’t available at this particular lab. Therefore, the tentative diagnosis of this case was marginal zone lymphoma (MZL), but it wasn’t possible to rule out splenic nodular hyperplasia completely.

Further treatment

Long was kept in the shelter while he recovered, so that the team could monitor his progress. Twenty days after surgery, a blood test was performed, in which the only abnormality was thrombocytosis (see Discussion).

At this time, a further two new masses were found at his left shoulder area, in addition to those originally found on his left thorax. These new masses were round, firm, and the overlying skin was normal. He was otherwise well, and all peripheral lymph nodes were normal.

Figure 5 - Purple arrow: original masses found on initial presentation. Blue arrow: new masses which developed after splenectomy.

FNA was performed on the new masses. The first sample was inconclusive, so the site was resampled. Results showed the new masses were also cutaneous histiocytoma. Cutaneous histiocytoma is a benign mass, which will often regress on its own, so Long was monitored for another month, during which the masses started to regress.

Case outcome and prognosis

The cutaneous histiocytomas eventually regressed completely. There were no masses present around six months after his initial presentation. Long was released back to his caretaker, so he could return to his original territory. He will be kept on a strict prophylactic ectoparasite regimen, to prevent babesiosis infection. There is limited evidence to predict survival time after splenectomy in MZL cases, but current research may suggest a survival time of at least 1-2 years (2). It is hoped that Long will have the opportunity to enjoy a good quality of life, living freely, but will be monitored by his caretaker and brought back for further treatment in the case of deterioration.

Discussion

Diagnostic Imaging

Radiography is a useful tool for investigating suspected splenomegaly. In this case, the images confirmed the increased size of the spleen and were suggestive of a splenic mass. It was felt that these radiographs, alongside clinical signs and the blood test, indicated surgery as the next step. The radiographs taken in this case were felt to be diagnostic, but technique could have been improved by more accurate collimation and centring.

In other circumstances, and if it is available, ultrasound can provide further information. Ultrasonography can provide further detail of the mass, and may provide clearer images especially if the radiographs are impeded by haemoabdomen. It may also be easier to look at nearby structures for evidence of metastasis.

Cutaneous histiocytoma

Cutaneous histiocytoma is a benign neoplasm and is common in dogs. This kind of mass originates from Langerhans cells (the antigen presenting cell in the skin). The condition usually occurs in young animals (mostly under 3 years old) and most cases spontaneously regress after a few months (often within three) (3). The typical appearance of a cutaneous histiocytoma is a small (usually < 2cm), erythematous, hairless nodule (3). They often appear more inflamed, and scab over when the mass starts to shrink down. This case was therefore an atypical presentation: the masses were larger in size, and there were no changes in the appearance of the skin.

Histiocytomas may be left without treatment, as most will resolve without intervention. If there are multiple masses, a course of prednisolone may be considered (at a dose of 1mg/kg PO SID), as was prescribed in this case. The course should be tapered off when the masses have resolved (3). The masses do not always cause irritation, but they may become pruritic, in which case a topical corticosteroid can ease symptoms. Surgical removal of the mass will cure the condition so can be considered in persistent cases where the mass becomes irritated or prone to secondary infection.

Marginal Zone Lymphoma (MZL)

Marginal zone lymphoma is a type of B-cell lymphoma which is named after its origin in the ‘marginal’ zone of lymphoid follicles. Knowledge about this condition in dogs is still developing, and much of what we presume is based on comparative information from human studies, where it is characterised as having a slow clinical progression (2). There are limited studies or published reports of dogs with this condition, which is in part because definitive diagnosis requires advanced pathological techniques (as was seen in this case).

Splenectomy is considered the treatment of choice for MZL, or any other neoplastic process in the spleen (1,4). As animals may live without a spleen, complete removal is usually performed in the case of suspected neoplasia during exploratory laparotomy. Neoplasia often has associated clinical signs such as bleeding and haemorrhage, which can also be managed by splenectomy. Surgical biopsy without complete splenectomy may be considered, but results positive for neoplasia will necessitate a further operation. It is currently unclear whether adjuvant chemotherapy improves survival time, and this is not always available in resource-limited settings (2,5). Dogs treated with splenectomy alone may survive with a good quality of life for several years, especially if they were asymptomatic on diagnosis or without comorbidities (2).

In this case, chemotherapy or prednisolone may have been considered if there was evidence of metastasis. Ultimately, all the other masses present were diagnosed as cutaneous histiocytoma, and there were no further pathological or clinical signs to suggest spread of the disease. Therefore, conservative management was followed.

Babesia

Babesiosis is a disease caused by a blood-borne protozoa, which is transmitted by tick bite. There are various species known to infect dogs, commonly, B.canis. Once in the blood, the protozoa invade red blood cells (erythrocytes). The infected erythrocytes display parasite antigens on their surface, triggering an immune response by the host. The resulting illness from Babesia infection is variable in severity, and depends on many factors, such as the host’s age, and the strain of Babesia present.

Animals who have had their spleen removed are more vulnerable to babesiosis (6). The spleen carries out major functions which are thought to help fight the disease, including acting as a store of red blood cells, producing lymphocytes, and removing damaged erythrocytes and antigenic particles from circulation (7). It is likely that the body’s resilience to the disease is compromised by splenectomy. Splenectomised individuals are more likely to exhibit severe symptoms such as anaemia and hepatopathy (6).

Babesiosis infection in splenectomised patients is often fatal (7). Measures to prevent infection are important in the immediate post-operative period, but also throughout the rest of the animal’s life. In this case, a course of doxycycline was used immediately after surgery, followed by a strict regimen of anti-tick medication long term.

Post-operative considerations

Patients should be supported peri and post-operatively with fluid therapy if possible. Haemorrhage after splenectomy may occur due to factors such as ligatures slipping (4). Monitoring patients post-operatively for signs of blood loss (especially into the abdominal cavity) can allow surgeons to act quickly if intervention is required. If there is no active bleeding, mild anaemia usually resolves with time. Cardiac arrhythmias may also occur post-splenectomy, so monitoring heart rate and rhythm post-operatively is advised (4).

Thrombocytosis was noted in this case, after splenectomy. Transient thrombocytosis is a known side-effect of splenectomy in humans. There is some evidence this can also occur in dogs (8). In humans, it is thought that platelet count may influence the risk of thrombotic complications, however this relationship has not been established in canine patients (8). Further research is required to evaluate the clinical significance of thrombocytosis in the post-operative period. One study has shown that platelet count is likely to normalise by two weeks post-surgery (8).

Key points

- Cutaneous histiocytoma is a common, benign neoplasm in dogs, which usually resolves without treatment.

- In cases of neoplasia of the spleen, splenectomy should be considered.

- Definitive diagnosis of MZL requires advanced pathology techniques, and clinical understanding of this condition in dogs is still in progress.

- It is important to prevent Babesiosis post-splenectomy (e.g. through regular ectoparasite treatment).

References

- Dobson, JM, (2011) Tumours of the spleen. In: Dobson, JM, Lascelles, DX, eds. BSAVA Manual of Canine and Feline Oncology, 3rd edn. Gloucester: BSAVA

- O'Brien D, Moore PF, Vernau W, Peauroi JR, Rebhun RB, Rodriguez CO Jr, Skorupski KA. (2013) Clinical characteristics and outcome in dogs with splenic marginal zone lymphoma. J Vet Intern Med. 27(4):949-54. doi: 10.1111/jvim.12116. Epub 2013 Jun 4.

- Rhodes, KH, Werner, AH eds (2018) Blackwell’s Five-Minute Veterinary Consult Clinical Companion: Small Animal Dermatology, 3rd edn. Hoboken: Wiley

- Niles, JD (2015) The spleen. In: Williams, JM, Niles, JD, eds. BSAVA Manual of Canine and Feline Abdominal Surgery 2nd edn. Gloucester: BSAVA

- Stefanello D, Valenti P, Zini E, Comazzi S, Gelain ME, Roccabianca P, Avallone G, Caniatti M, Marconato L. (2011) Splenic marginal zone lymphoma in 5 dogs (2001-2008). J Vet Intern Med. 25(1):90-3. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-1676.2010.0639.x. Epub 2010 Nov 23.

- Ayoob AL, Hackner SG, Prittie J. (2010) Clinical management of canine babesiosis. J Vet Emerg Crit Care (San Antonio). 20(1):77-89. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-4431.2009.00489.x.

- Camacho AT, Pallas E, Gestal JJ, Guitián FJ, Olmeda AS. (2002) Babesia canis infection in a splenectomized dog. Bull Soc Pathol Exot. 95(1):17-9.

- Phipps WE, de Laforcade AM, Barton BA, Berg J. (2020) Postoperative thrombocytosis and thromboelastographic evidence of hypercoagulability in dogs undergoing splenectomy for splenic masses. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1;256(1):85-92. doi: 10.2460/javma.256.1.85.

About the author

Dr Malisa Santavakul (aka “Lukpla”) has been working with WVS Thailand since April 2019, after graduating from Kasetsart University in Bangkok and working in the Raptor Centre.

She regularly mentors students (Thai and International) and she looks after Rescue Cases, both surgically and medically.

© WVS Academy 2026 - All rights reserved.