We use cookies

We use cookies to ensure that we give you the best experience on our website. Would you like to accept all cookies for this site?

Minnu, Inguinal hernia

Introduction

Minnu was presented to our WVS Clinic in Ooty, India, with a marked swelling in the ventral inguinal region. With immediate veterinary attention, diagnostic work-up, and surgical intervention, the team worked quickly to address her condition. This is Minnu's story.

History

Minnu, an intact eight-year-old, non-descript (Indie), female dog, was presented to WVS-ITC clinic, Ooty, with a two-week history of an enlarged swelling in her ventral abdomen.

Signalment

Female, intact, non-descript (indie) breed, weighing 16 kg and approximately 8 years of age. Her deworming and vaccination status were unknown.

Physical examination and clinical findings

Minnu was quiet, alert, and responsive. Auscultation of heart and lungs was unremarkable, and a physical examination of her abdomen revealed a soft, irreducible and non-painful mass in the left inguinal region covered with intact skin (Figure 1).

Figures 1 & 2 — Large, non, painful mass in the left inguinal region

Runni's clinical parameters were unremarkable: her heart rate was 64 BPM, respiratory rate 14 BPM, and body temperature 100.7°F (38.2°C). Her CRT was less than 2 seconds and mucus membranes pink and moist; her hydration status was therefore estimated at < 5% dehydration.

Differential Diagnoses

Based on the original clinical findings, the following list of differential diagnoses were considered:

- Inguinal hernia

- Mammary tumour

- Abscessation

- Lipoma

- Lymphadenopathy

- Haematoma

Diagnostic workup

Abdominal Radiography

A lateral abdominal radiography image demonstrated a loss of the caudal abdominal stripe and the presence of intestinal loops within the ventral mass as seen in Figure 2.

Figure 3 — Lateral abdominal radiograph showing the presence of intestinal loops in the soft tissue mass

Abdominal Ultrasonography

Ultrasonography of the ventral mass revealed a cross-sectional image of an intestinal loop within it as seen in Figure 3. Other abnormalities were not observed on further imaging.

Figure 4 — Abdominal ultrasonography revealed the presence of small intestinal loops.

Haematology and Serum Biochemistry

All parameters were within normal limits.

Definitive Diagnosis

Based on the imaging results and workup, a final diagnosis of inguinal herniation with displacement of small intestinal loops was made.

Treatment Plan

Treatment for inguinal herniation involves surgical closure of the abdominal wall defect following reduction of the intestinal loops back in the abdominal cavity.

The following protocol was used for premedication and anaesthesia.

Premedication. Xylazine (1mg/kg) + butorphanol (0.2 mg/kg) intramuscularly, followed by diazepam (0.25 mg/kg) slow IV, meloxicam (0.2mg/kg) IV and lignocaine +ketamine CRI

Pre-operative antibiotic. Amoxicillin-cloxacillin (20mg/kg) IV

Induction, Propofol (1mg/kg) slow IV

Anaesthetic maintenance. Isoflurane 2%

Surgery

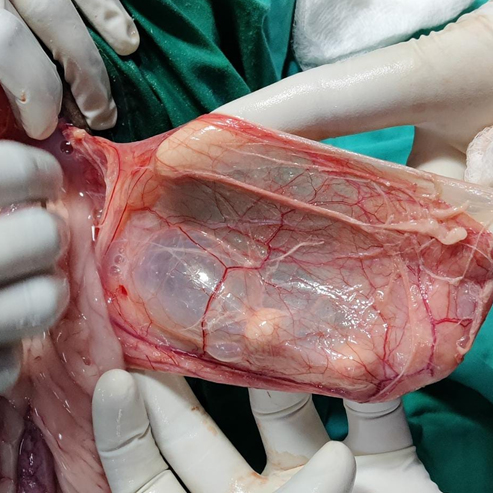

Minnu was positioned in dorsal recumbency. The surgical site was clipped and scrubbed with chlorhexidine followed by isopropyl alcohol spray. A caudal abdominal midline skin incision was made that extended cranially from the brim of the pelvis. The incision was deepened through subcutaneous tissues to the ventral rectus sheath. By bluntly dissecting beneath mammary tissue, the hernial sac and ring were exposed (Figures 5 & 6).

Figure 5 & 6 — Left image: Hernial sac containing intestinal loops. Right image: Hernial sac after intestines were gently reduced back to the abdominal cavity.

The herniated loops of intestine were gently reduced back into the abdominal cavity through the enlarged inguinal ring. The base of the hernial sac was then amputated and closed with horizontal mattress sutures in a simple continuous suture pattern with a monofilament, absorbable suture material, Polydioxanone [PDS] 2-0.

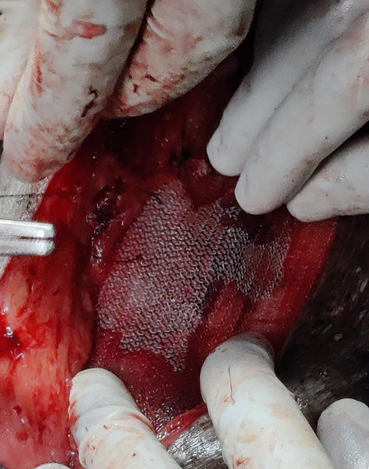

Following this, the hernial ring was closed with simple interrupted suture pattern using polydioxanone 1-0 (Herniorrhaphy). Since the hernial ring was large, a polypropylene mesh (knitted, non-absorbable) was used as an overlay to reinforce the primary hernia repair (Figure 7).

Figure 7 — The primary hernia repair was reinforced with a polypropylene mesh overlay.

Care was taken to avoid compromising external pudendal vessels and genitofemoral nerve, which exit from caudo-medial aspect of the ring.

An addition surgical incision was made along the ventral midline incision, and a spay (ovario-hysterectomy) was performed. The muscle incision was closed with polydixoanone 1-0, the subcutaneous layer was closed in a simple continuous pattern, and the skin was closed with an intradermal pattern with polydioxanone 1-0 (Figure 8).

Figure 8 — Closure of the surgical wounds

Post-operative Care

In the post-operative period, Minnu received analgesics (meloxicam — 0.1 mg/kg, SC) for 3 days. Post operative antibiotics were not given as it was a clean surgical wound and there was no break in asepsis during the surgery. An Elizabethan collar was used to prevent Minnu from biting or licking her surgical site. Strict rest and short leash walks were recommended for 2 weeks. Minnu recovered without any complications.

Discussion

A hernia refers to the abnormal protrusion of an organ or tissue through a normal or abnormal opening in the abdominal muscles or in the diaphragm. The term is commonly used to describe the protrusion of organs through the muscular part of the abdominal wall. In relation to inguinal hernias, these are characterised by the protrusion of intestines or other viscera through the inguinal canal. Inguinal hernias are not common in the cat but are fairly common in the dog, and particularly more frequently in bitches.

In the bitch, inguinal hernias are found most often in pregnant, aged, entire, obese, or those suffering from pyometra, whereby the hernial sac could contain a gravid or diseased uterus. In addition, traumatic events can result in inguinal hernias due to a congenital weakness of the musculature or abnormality of the inguinal ring.

Most inguinal hernias are unilateral; however, be sure to examine both sides in case the condition is bilateral. The most common presentation is when the hernial contents are soft, doughy, and painless on palpation. However, this does vary depending on the contents and length of time that the hernia has been present. Pain is often present when intestinal strangulation has occurred, or if a gravid uterus or urinary bladder is in the hernia.

With respect to diagnostic options, radiography is helpful to differentiate intestine, gravid uterus, or bladder in the hernial sac. This is often the most straightforward diagnostic method, and barium contrast material may be helpful if the digestive tract is involved. Otherwise, ultrasound is the quickest method if the option is available. Laboratory abnormalities are uncommon unless intestinal strangulation or rupture has occurred.

The goal of surgery is to reduce the abdominal contents back into the abdominal cavity, followed by closure of the external inguinal ring; this ensures that herniation of abdominal contents cannot recur. The approach used for inguinal hernias is dependent on whether the hernia is unilateral or bilateral, if the contents are reducible, and whether intestinal strangulation or concurrent abdominal trauma are present. Although an incision can be made parallel to the flank fold directly over the lateral aspect of the swelling, a midline incision is usually preferred in female dogs because it enables palpation and closure of both inguinal rings through just a single skin incision. Inguinal hernias can usually be closed without using prosthetic materials.

Monofilament absorbable (e.g., polydioxanone [PDS]) suture material should be used to close the hernial ring. Multifilament absorbable/non-absorbable suture may be associated with a higher incidence of wound infection. Mesh can be used as an overlay to reinforce the primary hernia repair. Routine use of drains is not recommended; however, hernial sites should be assessed postoperatively for evidence of infection or the formation of a hematoma or seroma.

Generally, the overall complication rate with inguinal hernias is very low with a low mortality rate. Therefore, the prognosis is excellent — that is, unless there are additional surgical complications such as intestinal strangulation or perforation have occurred.

Conclusion

Proper diagnosis and treatment resulted in a favourable outcome in the surgical management of the inguinal enterocele in Minnu. The surgical experience and preparedness of the WVS ITC team was of paramount importance in the successful outcome of this case.

References

- Fossum, T.W. (2013). Small Animal Surgery Textbook. Elsevier Health Sciences, pp. 512-39.

- Waters, D.J., Roy, R.G. and Stone, E.A. (1993). A retrospective study of inguinal hernia in 35 dogs. Veterinary surgery, 22(1), pp. 44-49.

- Monnet, E. ed. (2013). Small animal soft tissue surgery. John Wiley & Sons, pp. 265-72.

- Bojrab, M.J. (2011). Diaphragmatic, inguinal, & perinial hernia repair (Proceedings). Available at:

https://www.dvm360.com/view/diaphragmatic-inguinal-perinial-hernia-repair-proceedings

About the author

Dr. Sumanth Bedre is one of our senior vets at WVS ITC in Ooty, India and has been working with WVS since October 2020. He graduated with Bachelor's in Veterinary Science and Animal Husbandry (B.V.Sc & A.H) in 2016 and completed his Masters in Veterinary Pathology (M.V.Sc) in 2018. He is very much interested in emergency and critical care, he is actively involved in ITC activities and outreach projects.

© WVS Academy 2025 - All rights reserved.