We use cookies

We use cookies to ensure that we give you the best experience on our website. Would you like to accept all cookies for this site?

Peppe; Hip toggle surgery

History

An owned dog called Peppe presented at our clinic in Malawi with a history of suspected blunt trauma, causing lameness in his right hind leg. He had reportedly chased after monkeys and reappeared with the injury. The owner administered paracetamol and he was brought to the clinic two days after the trauma.

Signalment

- Age: 7-8 years old

- Weight: 40kgs

- Breed: GSD and Great Dane cross

- Sex: Neutered male

- Body condition: Ideal (5.5/9 scale)

Clinical signs

On examination, he was bright and alert, though reported to have a reduced appetite. His gums were pale pink, with a body temperature of 38.5°C. His lungs were clear, heart sounds were normal, but his heart rate was slightly elevated at 120 beats per minute, with tacky mucous membranes.

He was showing severe lameness (5/5) in his right leg, and was non-weight bearing. The leg was in an abnormal position and held higher than normal. In certain postures, it seemed shorter than the contralateral leg, with an inward curvature of the entire limb, though the stifle was pointing outward. He exhibited extreme pain and was reactive to examination.

Figure 1 Lameness; an inward curvature of the entire right hind limb with the stifle pointing outward

Differential diagnoses

- Hip luxation

- Femoral neck and head fractures

- Hip dysplasia

- Avascular necrosis of the femoral head (Legg Perthes disease), though less likely due to breed

Investigation and initial stabilisation

After the initial assessment, Peppe was sedated and given analgesia using a combination of medetomidine and methadone. Ketamine and diazepam were later administered for induction. Providing analgesia and anaesthesia enabled further examination.

The stifle was found to be rotated laterally while the tarsus was rotated medially. When the dog was placed on his back and the hind limbs were extended caudally, the affected limb appeared shorter than the unaffected limb. No instability or crepitus was noted on palpation of the distal limb.

Palpation and manipulation of the proximal limb revealed inflammation and crepitus in the coxofemoral joint. Additionally, while the dog was lying on his unaffected (left) side (in lateral recumbency), an abnormal position of the greater trochanter was observed. The orientation of the ilial wing, greater trochanter, and ischial tuberosity had changed, distorting the normal triangular anatomy of the hip. A noticeable increase in the distance between the greater trochanter and ischial tuberosity was also apparent, with the greater trochanter resting along an imaginary line between the ilial wing and the ischium.

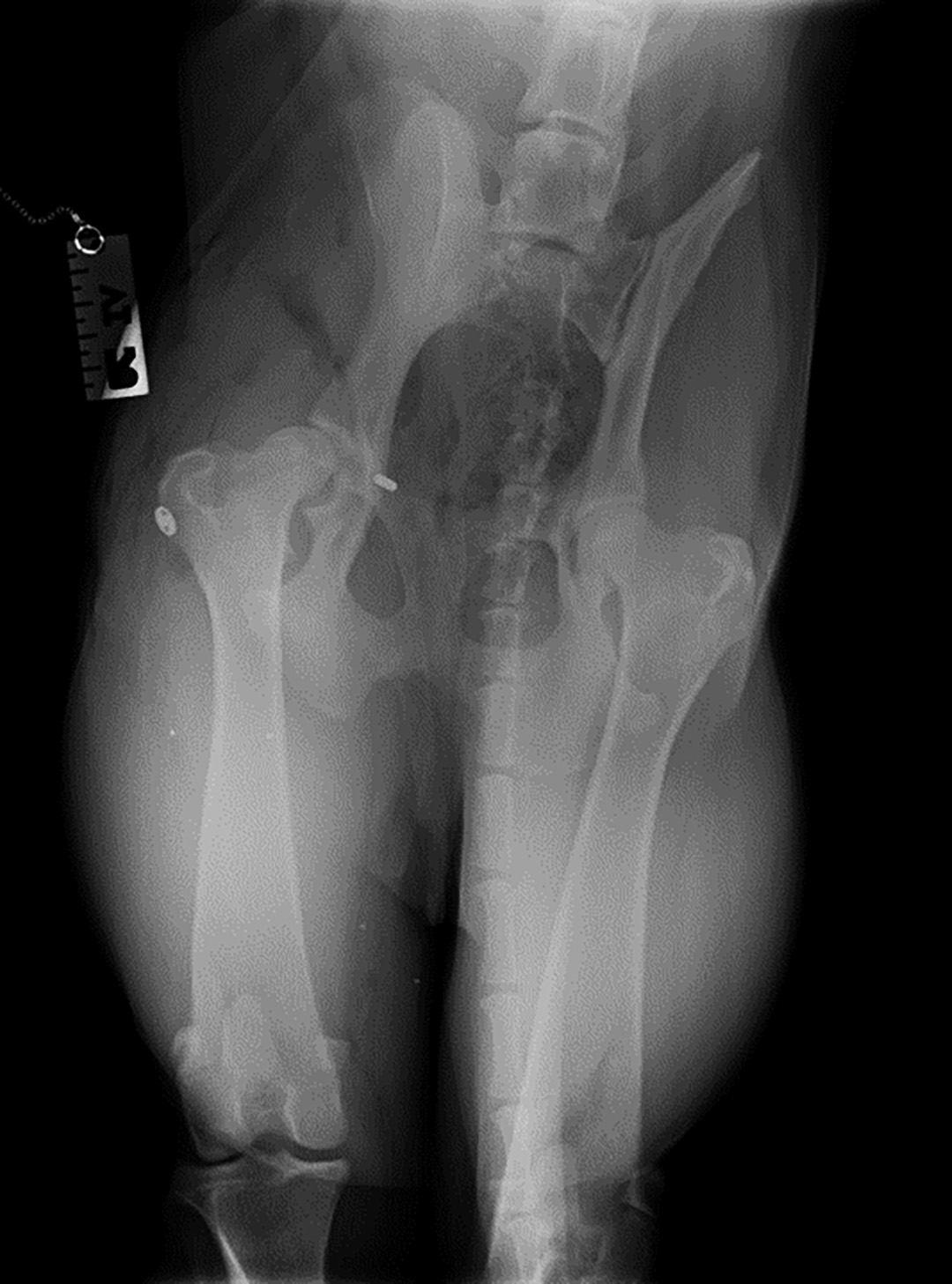

Radiographs were taken to confirm the presumptive diagnosis of hip luxation.

Peppe was put on IV fluid (sodium chloride) for mild dehydration at a rate of 2ml/kg/hr. In addition to the methadone he received in his premedication, he was given meloxicam and gabapentin for multimodal analgesia.

Diagnosis

On review of his radiograph, cranial dorsal hip luxation was confirmed. Abnormalities such as hip dysplasia, avascular necrosis of the femoral head (Legg Perthes disease), fractures on the femoral neck, head and great trochanter were ruled out.

Figure 2 Dorsoventral radiograph showing cranial dorsal luxation on the right side

Initial Treatment

In order to reduce the coxofemoral luxation, stabilise the joint and avoid further damage to the articular cartilage, closed reduction was attempted.

Closed reduction

A closed reduction procedure was attempted. The patient remained under general anaesthesia and was positioned in lateral recumbency with the affected limb on top. To begin, the limb was externally rotated to move the femoral head away from the ileum [1]. Then, distocaudal traction was applied to bring the femoral head closer to the acetabulum. Pressure was applied to the greater trochanter while the limb was internally rotated, attempting to reduce the femoral head into the acetabulum [1].

However, despite several attempts, the hip repeatedly dislocated, with the femoral head failing to stay in the acetabulum. The hip joint luxated with minimal force, leading to the decision that an open reduction would be the preferred treatment [1], [2].

Surgical treatment

Decision making for surgical treatment

Several treatment options were considered which included:

- Femoral head and neck osteotomy [3], [4], [5], [6]

- Reduction and capsulorrhaphy [3], [4]

- Ischioilliac pinning

- Transposition of great trochanter

- Hip toggle-pin technique [3], [4], [5]

- Transarticular pinning [4], [5]

- Fascia lata loop stabilization [7]

- Triple pelvic osteotomy [4], [5]

- Total hip replacement [4], [5]

- Extra articular illiofemoral suture placement

- Transposition of sacrotuberous ligament

Based on the authors experience, a femoral head and neck osteotomy was initially considered. However, this procedure was contraindicated due to the dogs breed and weight. Given the available resources and the surgeon’s expertise, a hip toggle procedure was chosen as the preferred treatment option and scheduled as soon as possible.

Stabilisation

Short-term fluid therapy included sodium chloride to stabilise mild dehydration. For pain management and inflammation control, meloxicam and paracetamol were administered upon arrival. Additionally, the patient was given methadone every four hours and gabapentin both before and after surgery for ongoing pain relief.

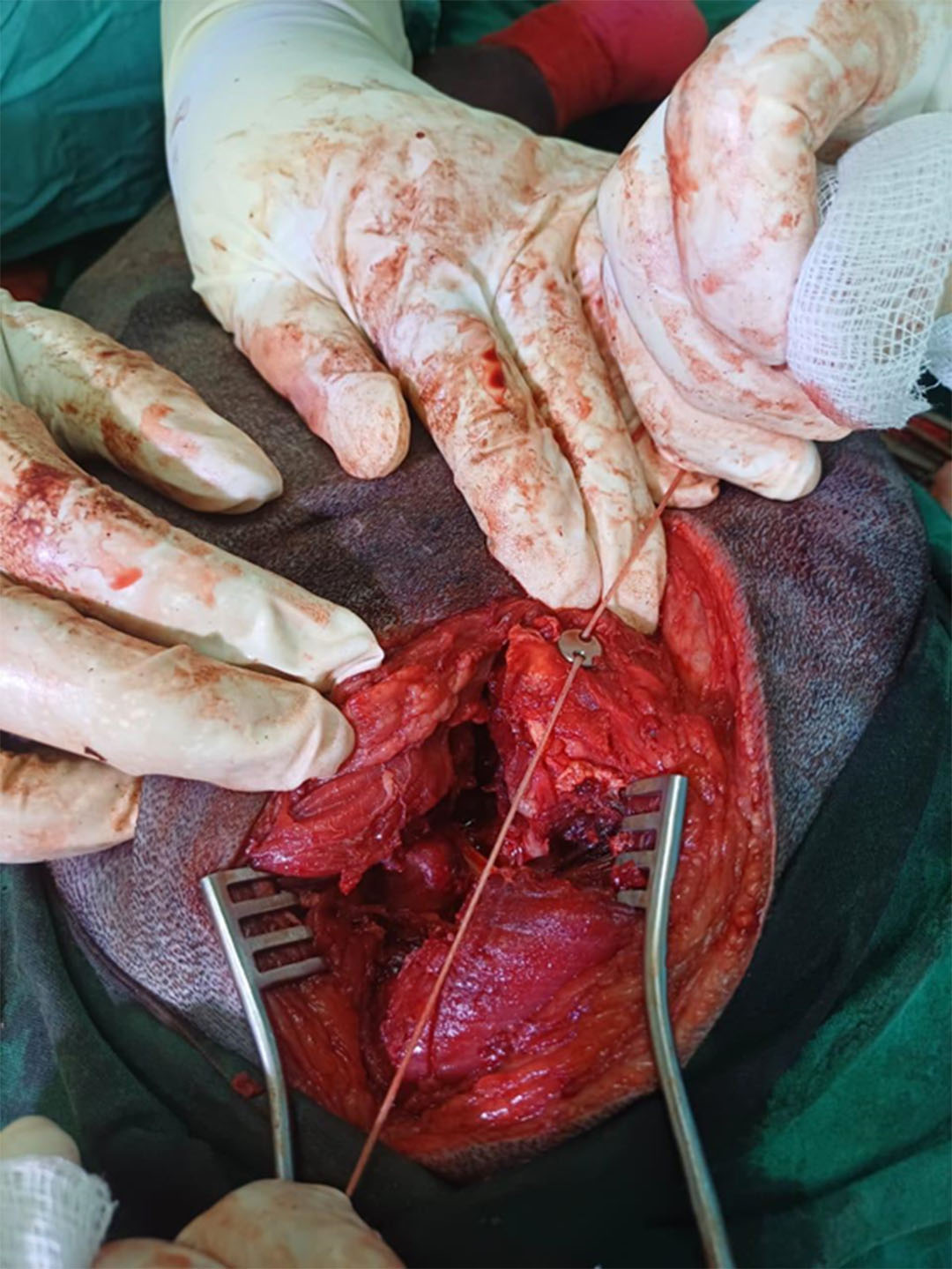

Hip toggle-pin repair

During the procedure, the patient received a continuous lidocaine infusion (CRI), IV fluids, and cefoxitin injections every 90 minutes. A cranial lateral approach was used to expose the acetabulum and femoral head (see discussion below). The hip was stabilised using a hip toggle. Capsulorrhaphy was performed and the wound was closed routinely.

Post-operative radiographs showed the femoral head positioned properly in the socket, and the prognosis for the hip toggle procedure is excellent.

Figure 3 Post-operative radiograph; hip toggle-pin on right side

Post-operative care

Following the surgery, primapore was applied to cover the wound for a day. Post operatively, he received fluid therapy, systemic antibiotics and pain relief.

Analgesia

- Methadone 0.3mg/kg

- Meloxicam 0.1mg/kg

- Paracetamol 10mg/kg

- Gabapentin 10mg/kg

Antibiotics

- Cefoxitin 20mg/kg during operation

- Cephalexin 15mg/kg after surgery

An Elizabethan collar was used to prevent him from biting or licking his surgical site. Rest and short lead walks were recommended for six weeks.

Prognosis and case outcome

Shortly after surgery, he began to put weight on the affected leg while standing. The next day, he showed interest and enjoyment in short walks on a lead.

Figure 4 Patient putting weight on the leg soon after recovering from anaesthesia

A month later, the patient came in for a follow-up and had continued doing very well at home. The owner sent videos of him very happy, running up and down, chasing other dogs.

Discussion

The toggle-pin repair technique involves drilling two holes: one through the centre of the acetabular fossa into the pelvic area, and the second from the fovea capitis through the femoral head and neck into the greater trochanter [2], [7], [8] . The prosthetic ligament, typically made of monofilament or braided materials like fiberwire or fibertape, is then used. The ligament is anchored to the centre of the acetabulum by a toggle pin (giving the technique its name) and secured to the greater trochanter of the femur with a button and a knot on top [2], [7], [8].

Indications for toggle-pin repair

- Chronic and acute hip luxations [4], [7], [8], [9]

- Multiple limb injuries [4], [7], [8], [9]

- Mild hip dysplasia [4], [7], [8], [9]

Suitability of the dog for surgery

General health status

Patients should be well enough to undergo the operation.

Preoperative assessment of the pelvis and the hip is extremely important prior to surgical treatment of a luxation [4], [5]. Key point to consider are:

- The direction of the luxation

- Other pelvic injuries that may influence the choice of technique [4]

- The presence and severity of hip dysplasia. A dysplastic hip may be more likely to re-luxate and this may influence the choice of the technique. Some surgeons will consider TPO and THR in such circumstances, but this may depend on other factors such as age, history, and economics [5].

- The presence of any avulsion or chip fractures of the femoral head

- The age of the patient. In theory, skeletally immature dogs that suffer luxation are at a risk of ischaemic necrosis of the femoral head if the capsular blood supply has been compromised [5], [6].

Risks of the procedure

- Drilling the rectum causing infection and rectal trauma

- Drilling the bladder causing bladder rupture.

- Implant premature breakage

- Insufficient joint stability

- Implant infection

- Re-luxation of the hip

Surgical method

Cranial lateral approach with tenotomy of deep gluteal muscles

The skin incision is centred at the level of the greater trochanter and the cranial border of the femoral shaft. Distally, it extends one-third to one-half the length of the femur, while proximally it curves cranially, stopping just short of the dorsal midline. Skin and subcutaneous fat are undermined and retracted to allow for an incision in the fascia lata along the cranial border of the biceps muscle [3], [5]. At the level of the greater trochanter, the incision curves cranially to follow the cranial border of the superficial gluteal muscles. Distally, it extends to the insertion of the tensor fascia lata muscle in the deep layer of the fascia lata [3], [5].

By retracting the biceps femoris and superficial gluteal muscles caudally, the greater trochanter is exposed. Cranial retraction of the tensor fascia lata reveals the cranio-ventral borders of the middle and deep gluteal muscles, exposing a triangular area bordered by the gluteal muscles, vastus lateralis, and tensor fascia lata. The middle gluteal muscle is retracted caudally, and an incision is made parallel to the fibers of the deep gluteal muscle to separate its caudal two-thirds from the cranial one-third [3], [5].

Severe damage to the joint capsule necessitated the use of the toggle-pin technique [4], [5].

Femoral neck tunnel, toggle-pin and suture insertion

A 3.5mm drill bit is used to create a hole at the upper end of the acetabular fossa, extending to the medial side of the pelvic area. The toggle pin is then inserted into the acetabular hole and pushed through to the medial side [4], [5]. The suture is pulled to ensure the toggle pin seats properly.

Next, a 2.0mm drill bit is used to create another hole through the femoral head and neck, starting at the fovea capitis and exiting laterally at the femoral shaft near the third trochanter. The size of the hole is determined by the animal’s size and the toggle pin being used [3], [5]. This smaller hole helps minimise devascularisation of the femoral head.

Using a 0.80mm Kirschner wire for guidance, the suture material attached to the toggle pin is passed through the tunnel. After the joint is reduced, a button is used to secure the end of the monofilament nylon to the proximal lateral surface of the femur at the level of the third trochanter [7], [8], [9].

Figure 5 Drilling a tunnel from the fovea capitis to the region of great trochanter

Figure 6 Securing the button by pulling the suture and tying a knot thereby reducing the luxation

Conclusion

Planning prior to orthopaedic surgeries along with multi-factorial consideration of the general condition of the patient and instrument availability will lead to a favourable outcome.

Key points

- Ventrodorsal and lateral radiographs of the pelvis should be obtained prior to attempting reduction, to evaluate direction of luxation, possibility of avulsion fractures of the teres ligament and other existing pelvic pathologies

- Closed reduction should always be attempted before considering open reduction, and is accomplished with a patient in lateral recumbency with injured limb uppermost

- Majority (90%) of traumatic luxations of the hip are craniodorsal in direction

- The synthetic round ligament that is created is not expected to function indefinitely, but it will maintain stability until the soft tissue damage in the region of the hip joint has undergone healing, with maturation of the scar tissue and re-formation of the joint capsule

- Dogs can have an excellent recovery and normal quality of life post hip toggle surgery

References

[1] Harasen Greg, 'Coxofemoral luxations part 1: diagnosis and closed reduction,' The Canadian Veterinary Journal, vol. 46, Apr. 2005.

[2] Bone David L, Walker Micheal, and Cantwell Dan H, 'Traumatic coxofemoral luxation in dog results of repair,' Veterinary Surgery, vol. 13, pp. 263–270, Oct. 1984.

[3] D. Piermattei and Frank. Giddings, n Atlas of Surgical Approaches to the Bones and Joints of the Dog and Cat, 3rd ed. saunders company, 1992.

[4] Piermattei Donald L, Flo Gretchen L, and DeCamp Charles E, Handbook of Small Animal Orthopedics and Fracture Repair, 4th Edition. Saunders Elsevier (Philadelphia), 2006.

[5] J. E. F. Houlton and British Small Animal Veterinary Association, Manual of canine and feline musculoskeletal disorders , 7th edition. Gloucester England : British Small Animal Veterinary Association, 2006.

[6] C. McLean, 'BSAVA Manual of Canine and Feline Musculoskeletal Imaging,' The Journal of small animal practice. , vol. 49, Oct. 2008.

[7] Jha Shantibhushan and Kowaleski Michael P, 'Mechanical analysis of twelve toggle suture constructs for stabilization of coxofemoral luxations,' Veterinary Surgery , vol. 41, Nov. 2012.

[8] Demko Jenipher L, Sidaway Brian K, Thieman Kelley M, Fox Derek B, Boyle Carolyn R, and McLaughlin Ron M, 'Toggle rod stabilization for treatment of hip joint luxation in dogs: 62 cases (2000-2005),' J Am Vet Med Assoc, vol. 15, Sep. 2006.

[9] Kieves Nina R, Lotsikas Peter J, Schulz Kurt S, and Canapp Sherman O, 'Hip toggle stabilization using the TightRope® system in 17 dogs: technique and long-term outcome,' Veterinary Surgery , vol. 43, Jun. 2014.

About the author

Dr Timothy Manda is Head Veterinarian and Clinic Veterinary Manager for the WVS clinic in Malawi. He has been working for WVS since 2021 and has a strong interest in soft tissue and orthopaedics; he particularly enjoys performing orthopaedic operations.

© WVS Academy 2026 - All rights reserved.