We use cookies

We use cookies to ensure that we give you the best experience on our website. Would you like to accept all cookies for this site?

Rummi, Cystolith and Cystitis

History

Rummi, a female, Labrador Retriever, was presented to our WVS ITC clinic in Goa, India with haematuria in the absence of any observable straining; the haematuria had been noticeable for 3 weeks. She was being fed a high protein diet and the owner reported that she drank only very limited amounts of water.

Signalment

A female, neutered, Labrador Retriever, weighing 37 kg and approximately 5 years old. De-worming and vaccination status up-to date. No history of other medical issues.

Physical examination and clinical findings

Rummi was bright, alert and responsive; she was classed as obese (BCS 5). Temperature (100.5 deg F/38 degC), heart rate (80 bpm without any murmur or arrhythmia) and breathing rate (30 bpm) were considered normal, with pink mucous membranes and normal CRT (<2 secs). Abdominal palpation did not reveal any abnormalities, and peripheral lymph nodes were considered normal upon palpation. She had a normal gait.

Differential diagnoses

Urolithiasis, cystitis/urinary tract Infection, urinary bladder mass, renal haematuria, coagulopathy (e.g. platelet disorder, liver disease)

Diagnostic workup

Urinalysis (naturally-voided sample)

| Colour | Red |

| Turbidity | Clear |

| Dipstick results | |

| Protein | Negative |

| Glucose | Negative |

| Bilirubin | ++ |

| Specific Gravity | 1.03 |

| pH | 8 (alkaline Urine) |

| Leukocyte | +25 |

Haematology and biochemistry

- Complete Blood Count (CBC) result was unremarkable. No signs of anaemia, leukocytosis or a thrombocytopaenia secondary to infection or inflammation.

- Serum biochemistry profile was within normal limits except for the following values:

| ALT(U/L) | 317 | 10-109 |

| BUN | 59 | 8-28 |

Ultrasound

Urinary bladder was enlarged to the presence of anechoic urine. A big calculus, approximately 2.5 cm diameter, was identified in the bladder lumen. The wall was thickened (1.5 cm) with a corrugated appearance. Both kidneys were normal.

Plain radiography

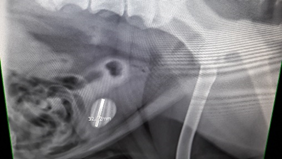

Lateral abdominal radiograph results correlated with the ultrasonography findings and revealed the presence of a 3 cm by 2 cm, radio-opaque calculi (Figure 1).

Figure 1 - Left, lateral abdominal radiograph showing the presence of a 3 cm x 2 cm cystolith. Right, higher magnification image of cystolith.

Definitive diagnosis

Cystolith with concurrent cystitis.

Treatment plan

Rummi was initially given meloxicam (0.2 mg/kg) SC and amoxicillin/clavulanic acid (15 mg/kg) PO BID for 7 days. The owner was advised to reduce the protein in her diet and provide ad-lib water (constant access). After the course of medications were complete, the surgical removal of the cystolith via cystotomy, was performed.

Surgical Procedure

The animal was presented by the owner on the day of surgery with an empty stomach, as advised. The following protocol was used:

Sedation. Xylazine (1 mg/kg) + butorphanol (0.2 mg/kg) injected intramuscularly

Induction. Diazepam (0.25 mg/kg) slow IV, followed by propofol (1mg/kg) slow IV

Pre-op multimodal analgesic protocol. Meloxicam (0.2 mg/kg) IV, lignocaine (1 mg/kg) IV and tramadol (4 mg/kg) IV

Pre-op antibiotic. Amoxicillin-cloxacillin (20 mg/kg) IV

After induction, Rummi was intubated with a size 10 cuffed ET tube and a urinary catheter was placed aseptically on the surgery table.

General anaesthesia maintenance. Propofol (1 mg/kg) slow IV approximately every 10 minutes, depending on the animal’s response to surgical stimuli

Cystotomy procedure

The animal was placed in dorsal recumbency. The surgical site was prepared aseptically and scrubbed with chlorhexidine followed by an isopropyl alcohol spray.

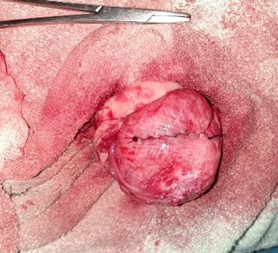

The urinary bladder was approached via a caudal, mid-ventral laparotomy. An incision was made on the mid-line, 7-8 cm below the umbilicus to 5 cm cranial to pelvic brim. The bladder was then exteriorised and isolated from the rest of the abdomen using sterile towels and gauze swabs in order to prevent potential contamination with urine (making sure the total number of swabs used was counted). The serosal surface of the bladder was markedly reddened with prominent vascular congestion (Figure 2).

Figure 2 - Exteriorisation of the bladder; with prominent inflamed surface.

Since the bladder was considerably distended, some of the urine was aspirated aseptically prior to starting the cystotomy procedure. A stab incision was made on a less vascularised area on the ventral aspect of the bladder and was extended approximately 2 cm using metzenbaum scissors. The remaining urine was drained and the large, oval calculi with smooth edges, was removed (Figure 3).

Figure 3 - Removed cystolith was large and oval with a smooth surface.

The bladder was then flushed multiple times using sterile saline to remove any remaining debris. The cystotomy incision was closed with 3-0 PDS using a Cushing suture pattern (Figure 4).

Figure 4 - Cystotomy wound closed with Cushings suture pattern.

A leakage test was performed which demonstrated good apposition of wound edges; a second layer of closure was therefore not performed. The towels/swabs used to pack the abdomen were then removed, ensuring that all swabs were removed by counting them carefully, and the abdomen was lavaged with sterile saline. The laparotomy incision was then closed routinely; the muscle and subcutaneous layers with PGA 1-0 in a simple continuous pattern, and skin with intra-dermal suture pattern using PGA 1-0) (Figure 5).

Figure 5 - Complete closure of the surgical site using intradermal suture pattern for the skin.

Post-operative care

Extended antibiotic and analgesic medications were given post-operatively to ensure a smooth and uneventful recovery:

- Post-op analgesia with meloxicam (0.1 mg/kg) SID for 3 days and tramadol (4 mg/kg) BID for 5 days

- Post-op antibiotic amoxicillin/clavulanic acid (15 mg/kg) BID for 7 days

- Dietary management comprised an easily digestible diet of boiled, plain chicken and rice with mashed carrot, pumpkin or broccoli

Follow up on day 3 revealed serum biochemistry profile was within normal limits, there was no haematuria and intradermal sutures were intact with a healing incision site. Urine pH was normal and negative for leukocytes.

A second follow up on day 10 revealed a well healed incision site and normal micturition.

Discussion

Urolithiasis refers to the presence of stones located anywhere within the urinary tract. Uroliths can develop in the kidney, ureter, bladder or urethra and are referred to as nephroliths, ureteroliths, cystoliths and urethroliths respectively.

The cystic calculi extracted was a struvite calculus as confirmed by stone analysis. Struvite stones are usually radio-opaque, and contain deposits of magnesium, ammonium & phosphate, often combined with bacteria. Urease-producing bacteria (Staphylococci spp & Proteus spp) located in the lower urinary tract commonly infect the bladder. They break down the urea into ammonia & bicarbonate. The ammonia combines with magnesium and phosphate to form struvite, whilst the bicarbonate increases the pH of urine. In alkaline urine, the struvite stones does not dissolve and the deposition results in cystic calculi (Brainbridge et al.,1996). Struvite cystoliths are most commonly found in certain breeds such as Shih Tzu, Dachshunds, Labrador retrievers and Miniature Poodles. Their recurrence rate of depends on whether there is a recurrent urinary tract infection.

In this particular case, the focus was to surgically remove the cystolith and treat the urinary tract infection. Therefore, Rummi was kept on amoxicillin potentiated with clavulanic acid to ensure that any bacteria located in the stones causing localised infection were removed. Penicillins are freely filtered in the kidneys, and actively secreted by proximal convoluted tubule cells into glomerular filtrate; therefore, urine concentrations are up to 300 times higher than plasma concentrations (Brainbridge *et al.*,1996), making them a good choice of antibiotics to use when targeting the urinary tract. The dissolution diet therapy wasn’t considered feasible due to the lack of availability of an acidified, prescription diet in Goa.

Cystotomy is the most convenient and recommended procedure to remove a big calculus which cannot be removed via other procedures, such as voiding urohydropropulsion, cystoscopic retrieval or lithotripsy, etc. The urinary bladder heals quickly achieving 100% strength in 3 weeks (Radasch et al, 1990). The apposition of wound edges result in a rapid gain in wound strength and does not reduce lumen size, provided that the mucosa is excluded. The use of monofilament suture material reduces the rate of infection as it does not absorb moisture, unlike braided multifilament.

Conclusion

The surgical approach of a cystotomy for stone removal, and antibiotic therapy, was found to be very effective in the management of a struvite cystolith and cystitis. There will always be a risk of recurrence of a struvite stone, and therefore regular monitoring is necessary. When the antibiotic sensitivity test is not available, it is always important to consider the lowest tier of antibiotic with the narrowest spectrum that will target the most likely type of bacteria, in order to preserve higher generations of antibiotics for future use.

References

Brainbridge, J., Elliott, J. & Davies, D. (1996), management of Canine and Feline Urolithiasia, BSAVA Manual of Canine and Feline Nephrology & Urology 1st Edition, British Small Animal Veterinary Association Kingsley House, Church Lane, UK, p209-220

Brown, S.A,2013, Urolithiasis in small animals, Mercks Veterinary Manual retrieved from https://www.msdvetmanual.com/urinary-system/noninfectious-diseases-of-the-urinary-system-in-small-animals/urolithiasis-in-small-animals?query=urolithiasis%20in%20dogs on 24th July 2020

Dvorska, J., & Saganuwan, S. A. (2015). A review on urolithiasis in dogs and cats. Bulgarian Journal of Veterinary Medicine, 18(1).

Ling, G. V., Franti, C. E., Ruby, A. L., & Johnson, D. L. (1998). Urolithiasis in dogs. II: Breed prevalence, and interrelations of breed, sex, age, and mineral composition. American journal of veterinary research, 59(5), 630-642.

Pope, E.R. (2016). Step-by-Step Cystototmy. Clinician’s brief, March 2016 Edition, 30-34

Radasch, R. M., Merkley, D. F., Wilson, J. W., & Bastard, R. D. (1990). Cystotomy closure: a comparison of the strength of appositional and inverting suture patterns. Veterinary Surgery, 19(4), 283-288.

Wendy Books, 2002 , Bladder Stones (struvite) in dogs, retrieved from https://veterinarypartner.vin.com/default.aspx?pid=19239&catId=102899&id=4951352&ind=25&objTypeID=1007 24th July 2020

About the author

Dr. Ranjita Bastola is one of our junior vets at the WVS ITC in Hicks, India. She graduated with Bachelor's in Veterinary Science and Animal Husbandry (B.V.Sc. & A.H.) in May, 2019 and joined WVS India where she has been working ever since. She enjoys her work very much and eventually would like to specialise in small animal medicine, as well as to travel different places for professional experience.

© WVS Academy 2026 - All rights reserved.