We use cookies

We use cookies to ensure that we give you the best experience on our website. Would you like to accept all cookies for this site?

Ovariohysterectomy versus Ovariectomy - which technique should I use?

Key points

Surgical sterilisation of dogs is one of the most commonly performed procedures in practice. Sterilisation of female dogs (spay) is considered an important skill for graduates entering clinical practice. Understanding the differences between ovariohysterectomy and ovariectomy will help the surgeon make an informed choice as to which method is appropriate for their patients.

Background

In simple terms, the complete surgical removal of both ovaries as well as the uterus is referred to as an ovariohysterectomy (OHE); by contrast, an ovariectomy (OVE) involves the removal of both ovaries whilst the uterus is retained.

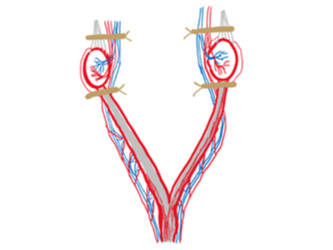

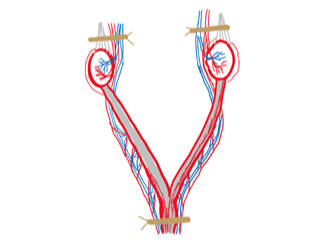

The basic surgical anatomy for both procedures is shown below (performed via a midline laparatomy).

Figure 1 - Clamp positions (left) and ligature positions (right) for an ovariectomy.

Figure 2 - Clamp positions (left) and ligature positions (right) for an ovariohysterectomy.

This spotlight article reviews the scientific literature for both procedures. It considers the advantages and disadvantages of each with respect to various key factors, and it explores the conditions to consider when deciding which procedure is appropriate to use for each patient.

Studies

The procedure itself

The reported total surgery time to perform both OVE and OVH varies in the literature; one study found that they both take a similar time of around 35 minutes and are of equal technical difficulty1, whilst others conclude that OVE is shorter as compared to OVH2,3. All three studies agreed that OVE surgery requires smaller skin incisions due to the removal of only the ovaries.

Multimodal pain management is an integral part of any surgical procedure; again, there is variation in published findings, with one study reporting pain scores to be lower in dogs that underwent an OVE2. However, postoperative pain and wound scores were shown to be similar for both procedures when assessed in a shelter scenario3.

Intra-operative complications

Both procedures carry an equal risk of developing ovarian pedicle haemorrhage. However, there is an increased risk of haemorrhage from vessels within the broad ligament and uterine vessels near the cervix when performing an OHE, whilst this step is absent during an OVE4. It is important to recognise that complications such as haemorrhage occur more frequently in either procedure during surgeries performed by an unskilled surgeon5; therefore, appropriate supervision should always be available. Additional differences in complication rates both intraoperatively, or up to 24 hours postoperatively, have not been reported in either procedure2,3.

Post-operative abnormalities

Urinary Sphincter Mechanism Incompetence (USMI). Neutering can increase the risk of development of USMI due to the reduction in circulating sex hormones, which can adversely affect voluntary urinary control via the urethral sphincter. Long term prospective studies have concluded that there is no difference in the occurrence of USMI in dogs after undergoing either procedure4.

Ovarian Remnant Syndrome (ORS). Another potential long-term complication is ORS which occurs when ovaries are incompletely removed, with residual ovarian tissue remaining functional due to collateral circulation6. One study reported that ovarian remnants tend to be more common on the right side which may be due to the cranial and deep location of the right ovary, making it more challenging to fully access4. The authors suggested that ORS is less likely to develop after OVE due to the more cranial location of the incision, which may allow improved exposure of the ovarian pedicle. There is evidence that ORS is more common with inexperienced surgeons and therefore, regardless of the technique, the surgeon’s skill is important in preventing ORS7. Inexperienced surgeons may have more opportunity to practice tissue handling and ligature placements when performing a full OHE, and this may reduce the incidence of retained ovarian tissues when compared to performing OVE surgery8.

Mammary tumours. Mammary tumours are more likely to occur in bitches that are not spayed, or are spayed after 2 years of age. The likelihood for developing a mammary tumour is 0.5% if spayed before the first heat, 8 % after the first heat and 26% after their second heat. These values are the same regardless of which technique is used4.

Cystic Endometrial Hyperplasia (CEH) and Pyometra. A retrospective cohort study comparing the long-term effects of OHE vs OVE in bitches found that there was no difference in the risk of development of CEH complex and pyometra/stump pyometra with either technique, with the complete removal of both ovaries9. The risk is considered comparable to that associated with ORS as it is the presence of circulating hormones that are implicated in the development of CEH complex and pyometra.

Uterine tumours. Although uterine malignant neoplasia is a risk, in reality it is extremely rare (with an incidence of 0.003%)10. By performing an OVE, this risk is eliminated with removal of the uterus. However for an OVH, the risk of development of uterine benign or malignant neoplasia is present but surgery is almost always curative and has an excellent prognosis in the absence of metastasis4.

Application

Both OVE and OVH procedures are suitable to use in clinical practice. The choice depends on a number of factors:

- The individual surgeon’s experience, preference and capabilities. The surgeon must feel confident in his/her abilities for a particular procedure.

- The clinical status of the patient; for example an OVE would be an option if uterine abnormalities are not observed during laparotomy11.

- The circumstances of the animal; for example, whether it is owned or is free-roaming.

In clinical practice, both procedures may be considered based on the factors discussed above. In a spay-neuter setting, however, OHE is the procedure of choice. This is because the majority of these dogs are free roaming and without owners who regularly check them. Their clinical history, pregnancy status or reproductive tract abnormalities will be largely unknown. Therefore, a standard protocol of performing OHE is chosen to eliminate potential, long term issues related to a retained uterus. WVS protocol recommends an ovariectomy only in young bitches who have not had their first oestrus yet.

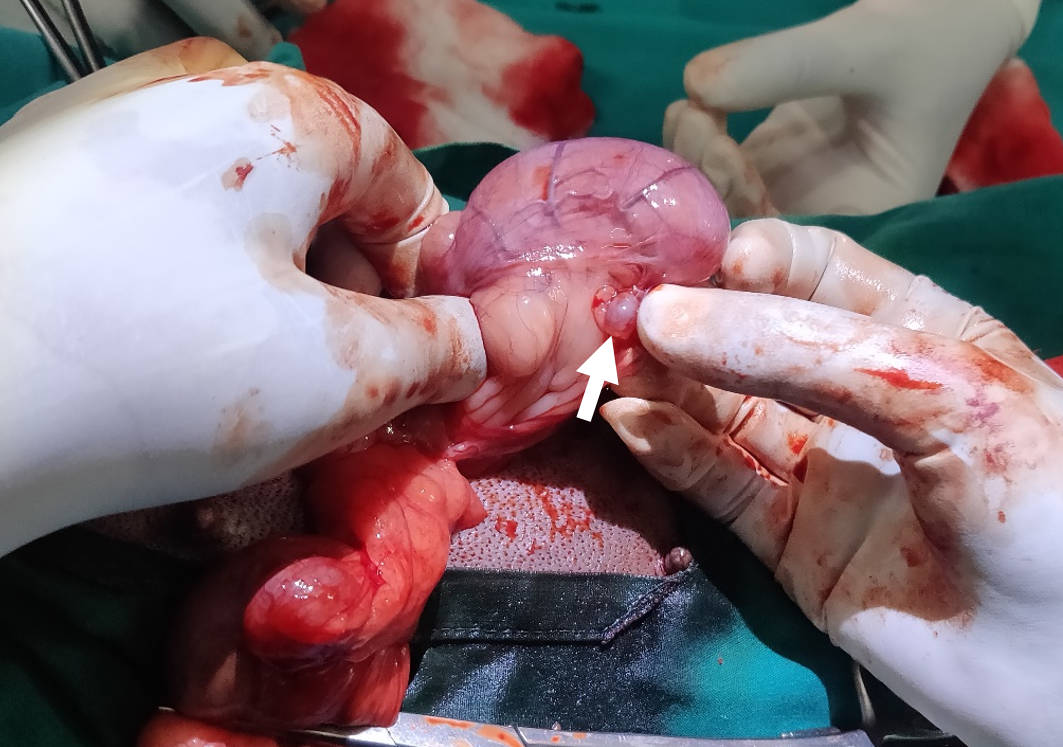

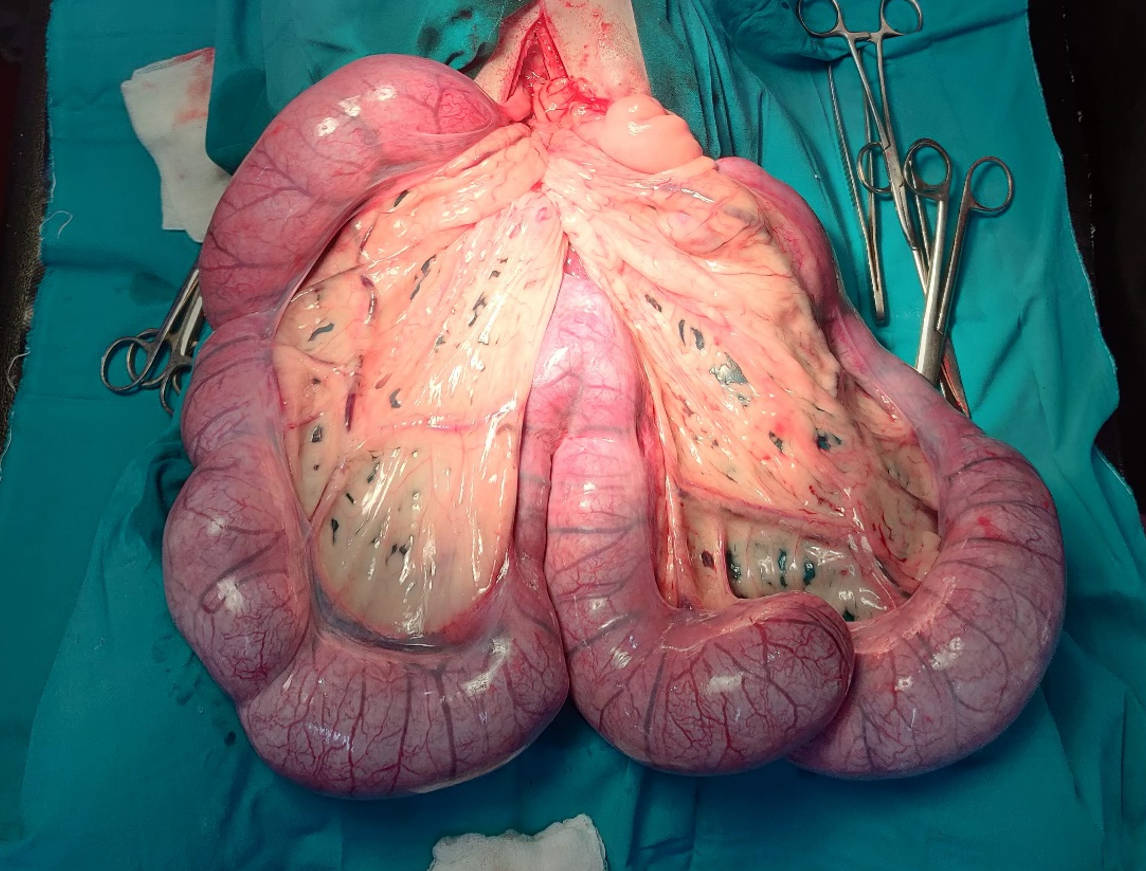

Examples of possible complications that warrant an OHE procedure are shown below:

Figure 3 - A cystic ovary (arrow) and enlarged, fluid-filled uterus.

Figure 4 - An enlarged, doughy uterus which was found to contain large amounts of purulent material (pyometra).

Conclusion

Both techniques are appropriate to use for surgical sterilisation in dogs. However, the choice of method should depend on the factors discussed above to ensure the best and safest surgical outcome for each individual patient.

Author

Dr Shruti is a Senior Taskforce Veterinary Surgeon. She enjoys teaching surgery to her students at ITC Ooty and loves travelling. Dr Shruti is passionate about animal welfare and 'One-Health' topics and hopes to become an epidemiologist someday.

References

- Peeters M.E., Kirpensteijn J. (2011) Comparison of surgical variables and short-term postoperative complications in healthy dogs undergoing ovariohysterectomy or ovariectomy. J American Veterinary Medical Association 238, 189–194.

- Lee, S., Lee, S., Park, S., Kim, Y., Seok, S., Hwang, J., Lee, H. and Yeon, S. (2013). Comparison of Ovariectomy and Ovariohysterectomy in terms of postoperative pain behaviour and surgical stress in dogs. Journal of Veterinary Clinics. 30 (3), 166-171.

- Tallant, A., Ambros, B., Freire, C. and Sakals, S. (2016). Comparison of intraoperative and postoperative pain during canine ovariohysterectomy and ovariectomy. The Canadian Veterinary Journal. 25 (7), 741-746

- VAN GOETHEM, B.V., SCHAEFERS-OKKENS, A., and KIRPENSTEIJN, J. (2006) Making a Rational Choice Between Ovariectomy and Ovariohysterectomy in the Dog: A Discussion of the Benefits of Either Technique. Veterinary Surgery. 35 (2), 136-143.

- Burrow, R., Batchelor, D., and Cripps, P. (2005) Complications observed during and after ovariohysterectomy of 142 bitches at a veterinary teaching hospital. Veterinary Record 157, 829–833.

- Fingland, R.B. Ovariohysterectomy, in Bojrab, M.J. (eds): Current Techniques in Small Animal Surgery (ed 4). (1998) Baltimore, MD, Williams & Wilkins, 489–496

- Pearson, H. (1973) The complications of ovariohysterectomy in the bitch. Journal of Small Animal Practice 73; (4) 257–266.

- Hoad, J. (2018). Spaying bitches: why, when, how? Available at: [https://www.theveterinarynurse.com/review/article/spaying-bitches-why-when-how] Accessed 10th June 2021.

- DeTora, M., and McCarthy, M.J. (2011) Ovariohysterectomy versus ovariectomy for elective sterilization of female dogs and cats: is removal of the uterus necessary? Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association 239 (11) 1409-12.

- Klein, M.K. Tumors of the female reproductive system, in Withrow SJ (eds): Small Animal Clinical Oncology (ed 2). Philadelphia, PA, Saunders, (1996), 351.

- Pennington, C. (2020) In female dogs undergoing elective neutering is ovariectomy or ovariohysterectomy superior? Veterinary Evidence 5 (2) 1-16

© WVS Academy 2025 - All rights reserved.