We use cookies

We use cookies to ensure that we give you the best experience on our website. Would you like to accept all cookies for this site?

Tob, Perianal Gland Adenoma

Introduction

Here is the story of a dog named Tob, a community dog whose caretaker noticed a mass on his bottom which was causing intense irritation.

History

Tob, a community dog, lived in a local market within the same district as the WVS Thailand Rescue and Rehabilitation Centre. His caretaker noticed that he had had a mass near his anus for several years which hadn't previously bothered him. However, the mass ruptured and began to irritate Tob 2 days before his caretaker decided to bring him for an assessment and treatment.

Signalment and Clinical Signs

Tob was an intact male dog, mixed-breed, 5 years old. He was initially very scared of our veterinary team and reacted with fear aggression; however, once he became familiar with the staff and his surroundings, he became a friendly and energetic dog. He had no history of vaccination or deworming. Since the mass located at a sensitive part of the body, the veterinarian-in-charge decided to sedate Tob for his initial full examination, to avoid unnecessary anxiety and pain.

Clinical findings

- Alert and responsive

- Defecating, urinating, drinking, and eating: all normal as reported by the caretaker

- Body weight: 11.5 kg; Body temp: 37.7°C

- Cardiovascular: pale pink mucous membrane colour, CRT < 2 sec, normal hydration status, normal heart sounds

- Respiratory: normal lung sound, RR 24 breaths per min

- Skin: found a ruptured mass on right anal sac area, necrosis on the tip of the lesion, margin of the mass quite close to the anal opening. The mass shape was round, firm, non-attached, size 3.5 x 3.0 cm (Figure 1).

- Body Condition Score: 4/5

- No ectoparasites were found

Figure 1 — The picture of Tob's mass on the first day after cleaning and applying silver sulfadiazine cream under sedation. From the picture you can notice the large size with inflammation. The black asterisk is the anus.

Differential Diagnosis

- Anal sac impaction and rupture

- Neoplasia; anal sac neoplasia, perianal gland neoplasia, mast cell tumour, or melanoma.

- Blood parasite infection (comorbidity)

Initial Diagnostic Work Up

Blood test: Complete Blood Count and blood chemistry

Fine needle aspiration (FNA)

Samples was taken via FNA of the mass under sedation.

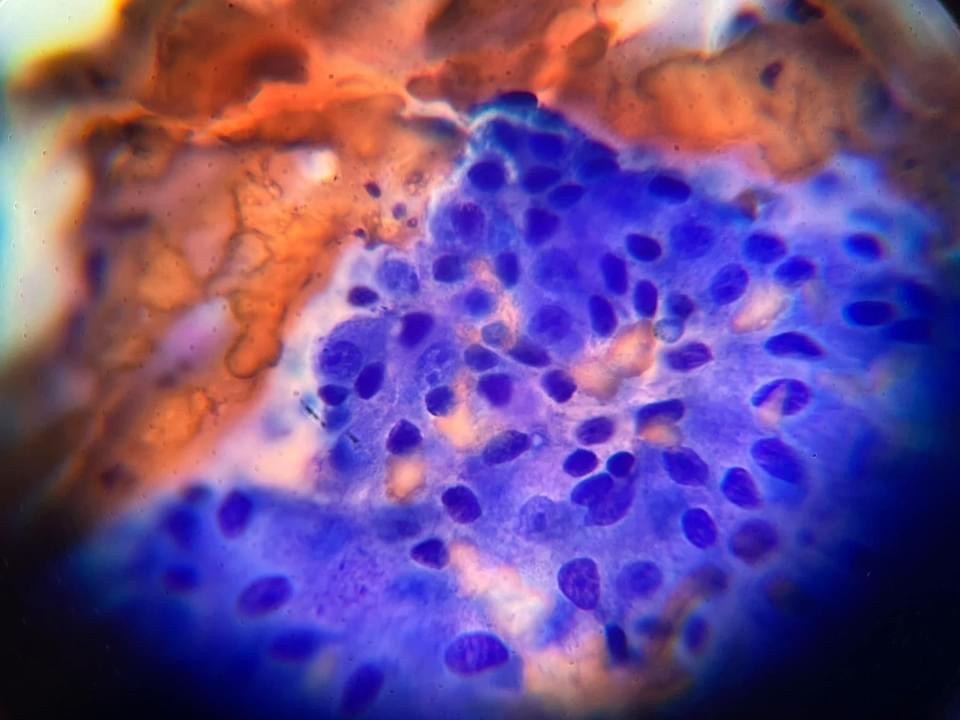

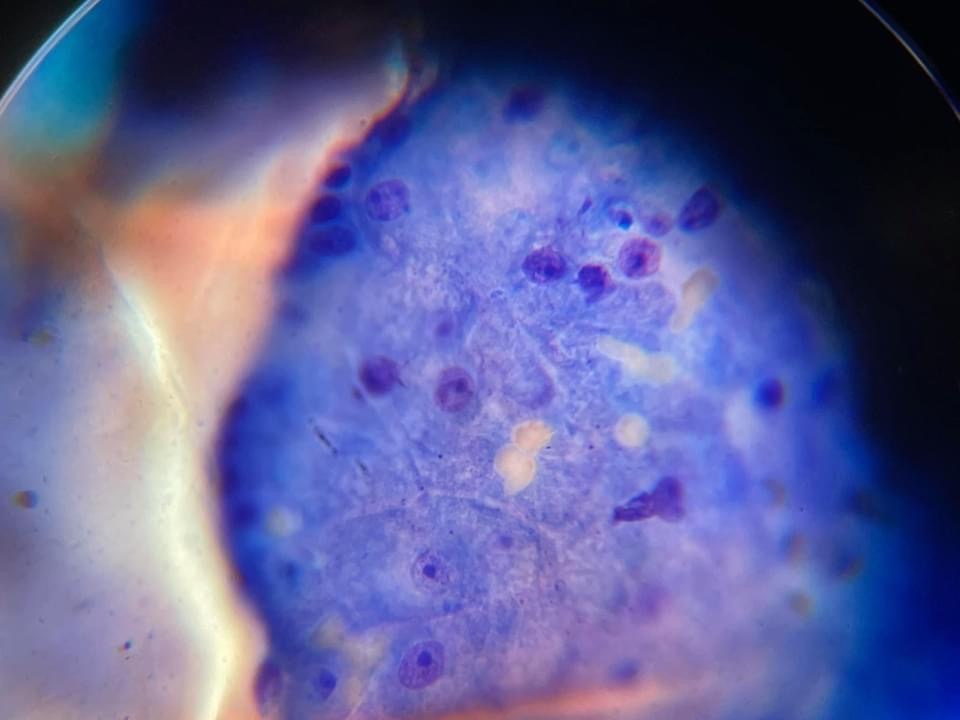

Figures 2 & 3 — Image from another case showing typical cytological features of a perianal gland adenoma with round to polygonal cells with similar appearance to hepatocytes.

Initial Treatment Plan

As the mass had ruptured and was painful and infected, and Tob was also Ehrlichia spp positive, the WVS vet decided to treat the pain and infection first, moving onto the surgical treatment plan after he was comfortable and his blood values had improved.

Tob had a dedicated caretaker who believed they could give him his medication; as such, he was discharged with:

- Amoxicillin-clavulanic acid: 187.5mg BID PO for 10 days

- Carprofen: 50 mg SID PO for 5 days

- Once the amoxicillin-clavulanic acid course had finished, a doxycycline course of 150mg SID PO for 28 days was administered to treat the Ehrlichia infection.

Fortunately, the caretaker followed the vet's suggestions carefully and correctly.

Tob was booked in the clinic for a blood check on days 14 and 28 of his doxycycline course to monitor his blood values, in order to determine when surgery would be appropriate for his perianal gland adenoma.

Secondary Diagnostic Work Up

Blood test: Complete Blood Count and blood chemistry

Tob's blood results for both on days 14 and 28 of doxycycline course were both negative for Ehrlichia spp. In addition, his other other blood parameters were within the normal range.

FNA: Second, smaller mass at base of tail

The reduction in the size and inflammation of Tob's primary perianal gland adenoma revealed a secondary, smaller mass at the base of his tail. This was confirmed by FNA to be another benign perianal gland adenoma.

Secondary Treatment Plan

With Tob's blood results had returned to within a normal range and the infection of the mass resolved, he was ready for castration and mass removal surgery. Tob was admitted for surgery. Beforehand, the staff noted that he frequently barked and looked at his rear throughout the day indicating discomfort from the mass (Figure 4).

Figure 4 — Tob's mass size after his antibiotic treatment. The mass has significantly reduced in size from the initial presentation and the ulceration had resolved. The white asterisk marks the anus.

The veterinary surgeon decided not to remove the smaller, perianal gland adenoma at the tail base, planning to monitor its size one month after castration. The reason for this decision was that the larger mass in the perineal area irritated Tob and removing this would resolve the primary irritation. However, the mass at tail base was not detectably irritating. If both masses were removed simultaneously, an extended anaesthesia time would be required with an increased risk of complications. The decision was made that if within one to three months after castration, the mass at dorsal tail still remained or if there were any signs of discomfort shown by Tob, the second surgical removal would be scheduled.

Treatment

Mass Removal and Castration

Normal sedation and anaesthesia preparation protocol was used and maintenance of anaesthesia was with 1% isoflurane.

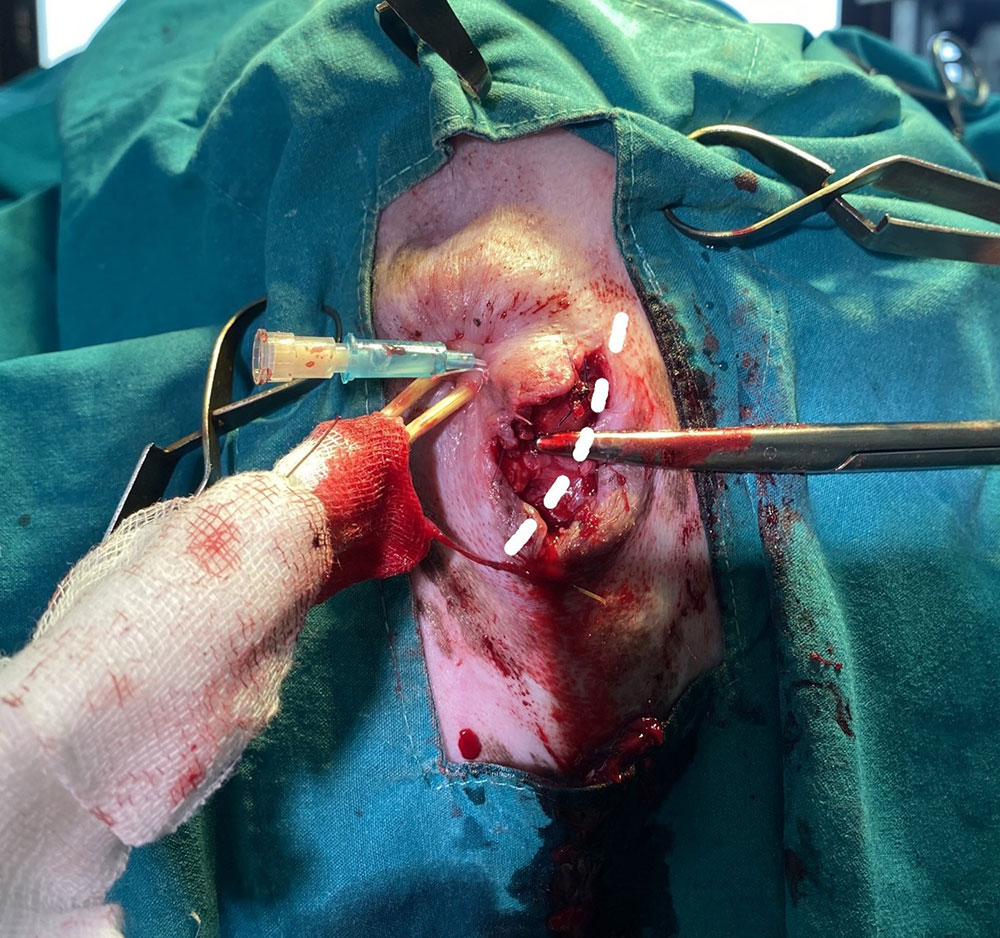

The castration was performed first. Tob's position was changed to sternal recumbency (with both hindlimbs hanging down from the surgery table) and the tail was tied cranially to keep it out of the surgical field. After removing faeces and re-scrubbing the anal area, 2 cotton sticks were inserted into the rectum and a purse string suture with a non-absorbable synthetic suture (Supramid 2/0) was placed around the anus to prevent contamination of the surgical field. A 22G IV catheter was inserted into the right anal sac opening, which was used to fill the anal gland with sterile saline and make it easier to palpate and therefore avoid (Figure 5).

Figure 5 — The anus with purse string closure and two cotton sticks inserted into the rectum to prevent rectal fluid leakage while doing the surgery, the clean sticks were wrapped by sterilize gauze, so that the vet surgeon can control the stick position. The dash line shows the incision line, parallel to the external anal sphincter muscle.

The perianal mass was located near the right anal sac (at 4-5 o'clock). A slightly curved incision was therefore made over the mass parallel to the external anal sphincter. The mass was carefully separated from the skin, taking care not to damage the surrounding tissue containing nerves to the anal sphincter. Damage to these nerves could lead to a dog becoming faecally incontinent. Because the mass was very peripheral (just under the skin), there was no damage to the anal gland or external anal sphincter.

The small artery supplying the mass was ligated with absorbable synthetic suture (Monocryl 4/0) and roughly 95% of the mass was able to be removed because the mass was very fragile. The initial FNA results indicated that castration is likely to reduce the size of this benign mass and, as such, exact margins, while optimal, were not essential. The removed mass was sent to the laboratory for confirmation.

The subcutaneous layer and intradermal layer were closed with absorbable synthetic suture (PGA 3/0) using a simple continuous and intradermal pattern respectively. Simple interrupted sutures were then used as external skin sutures with PGA 3/0 (since Supramid 2/0 is too big for closing perianal skin) because the skin was under slightly more tension than was optimal to be confident that the intradermal layer would be sufficient to prevent dehiscence (Figure 6).

Figure 6 — Photo taken post-op. This picture shows the positioning of the dog for surgery of the perineal area (another option for a larger dog could be in ventral recumbency, bringing both hind legs forward to save the hip joints but still providing a good surgical field). The picture also shows the incision line that the vet surgeon cut parallel to the external anal sphincter. The black dots show the positions of both anal sac openings.

The surgical wound was cleaned, silver sulfadiazine cream was applied, and an Elizabethan collar was secured to prevent Tob from accessing the wound (Figure 7).

Figure 7 — Tob with an Elizabethan collar to prevent him licking the wound

Post-operative medicine was prescribed:

- Amoxicillin-clavulanate (375): ½ tab BID PO for 10 days

- Carprofen (75): ½ tab SID PO for 5 days

The antibiotic was prescribed as prophylaxis due the surgical wound being very close to the anus opening, and there being a high risk of infection of the surgical site.

Post-Op Wound Progression

For the 1-3 days after surgery, Tob was carefully observed to make sure that he didn't have difficulty or pain when defecating, or signs of incontinence. Fortunately, there were no problems noticed by the team (Figure 8).

Figure 8 — The first day after the surgery, the surgical wound showed mild inflammation (wound score 1/4) but the skin was still well apposed.

His castration wound had a wound score of 1/4 and a pain score of 0/10 the day after the procedure, and the mass removal wound had a wound score of 1/4 and a pain score of 0/10. However, the mass removal wound dehisced 3 days after the surgery (Figure 9).

Figure 9 — Day 3 after the surgery: part of surgical wound started to dehisce and became infected. Unfortunately, this is a common complication in this region and needs to be monitored closely with frequent wound cleansing. The black asterisk is the anus.

Therefore, daily wound treatment was started with the plan to allow the wound to heal by second intention. The wound was flushed daily with sterile saline under pressure, and topical silver sulfadiazine cream was applied. The remaining external sutures were removed.

For the first week after surgery Tob showed some discomfort with his wound, but it reduced with time and eventually resolved (Figure 10).

Figure 10 — Day 8 after the surgery: the external sutures were removed, the surgery wound has not completely closed at the most caudal aspect beneath the anus, but this section showed good granulation tissue with mild dry serous discharge. Thus, the decision was made to allow it to heal by second intention.

The open wound healed by the 13 day after surgery (Figure 11).

Figure 11 — Day 13 after the surgery: the surgery wound is completely healed.

Prognosis

Perianal gland adenomas are androgen hormone dependent, so castration can reduce recurrence, and also the mass size. Prognosis after total mass removal without regional lymph node involvement (sublumbar lymph node) is good to excellent and without the need for chemotherapy.

Outcome

After the perianal gland adenoma was removed, Tob changed from an aggressive to a friendly dog and he could go back to his community and enjoy his life. The WVS Thailand Rescue and Rehabilitation Centre still keep in touch with Tob's caretaker to monitor the mass at his tail base. Tob will come back to see our vets and staff for mass monitoring soon.

Discussion

Perianal tumours can originate from two main glands; the apocrine anal sac glands and the perianal or circumanal glands (so called, hepatoid glands). Other tumours that can occur at perineal area are melanoma, mast cell tumour, and lymphoma.

Apocrine anal sac gland neoplasia

The adenoma form is extremely rare, while the adenocarcinoma form is quite common. An adenocarcinoma's appearance is invasive, between 0.2-10 cm diameter, has a typical metastatic pattern (usually metastasis to sublumbar or intrapelvic lymph nodes), and paraneoplastic hypercalcaemia occurs in up to 30-50% of the cases. This small tumour can be detected with careful rectal palpation examination while the larger tumour is often noticed from a bulging of the perineal area. Large tumours are often accompanied by the dog showing clinical signs of constipation, tenesmus and haematochezia. A case that has concurrent paraneoplastic hypercalcemia may show; polyuria/polydipsia, lethargy, anorexia, weight loss, weakness, bradycardia, vomiting, and in severe cases, renal failure.

Cytology is usually sufficient to establish a definite diagnosis of an anal sac gland tumour, but careful staging is recommended. Staging includes: a digital rectal exam, a complete blood count and blood chemistry (especially calcium level), thoracic radiography and abdominal ultrasonography (especially caudal abdominal). If available, computer tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is superior to ultrasonography in detecting sublumbar and intrapelvic metastasis, and it is very useful for surgical treatment planning.

Treatment for anal sac gland tumours includes surgical treatment with radiation and/or chemotherapy. A wide local resection is recommended in adenocarcinoma type tumours (sometimes the tumour cannot be completely removed with reasonable margins due to the tumour location). Regional lymph node removal may also be required (sublumbar and intrapelvic lymph nodes). A possible complication after wide local resection is transient or permanent faecal incontinent. Castration has no benefit for this type of tumour.

Circumanal/perianal gland/hepatoid gland neoplasia

The carcinoma form of this tumour is much less common than the adenoma form. Normally, hepatoid glands are present primarily in the perianal area, but to a lesser degree they can also be found in other body regions; e.g. base of the tail, vulva, prepuce, hind legs and caudal dorsum. Their cells contain receptors for androgens and oestrogens, as well as growth hormone, and it is known that the growth and function of these glands are regulated by sexual hormones. Both carcinomas and adenomas of hepatoid glands contain androgen receptors. Intact male dogs and spayed female dogs are predisposed to perianal adenoma development. Carcinomas affect predominantly intact male or late castrated males. Usually, older dogs are affected. Many dogs have concurrent testicular tumours. Adenomas of the hepatoid glands present as solitary or multiple, sometimes ulcerative masses in the perianal or preputial area, which can be secondarily altered by infection and auto mutilation. Since the signalment and clinical appearance of perianal adenomas are very characteristic, the tumours can usually be easily recognized. Malignant forms can look similar to adenomas, but usually they are more infiltrative and have a more aggressive clinical appearance. A protracted course of disease, lasting up to one year, is not uncommon.

Carcinomas are difficult to differentiate from adenomas by cytology, since even adenomas may have fairly pleomorphic cellular characteristics. A careful digital rectal exam is indicated in all perianal tumours and includes the assessment of the degree of invasion, palpation of the prostate and the sub lumbar lymph nodes. The testicles should also be examined by palpation or ultrasonography. If a carcinoma is suspected, ultrasonography of the caudal abdomen and thoracic radiographs to finding the metastasis are indicated.

The therapy of choice for small, nonulcerated tumours in sexually intact males is castration. Surgical resection is indicated in ulcerated or bleeding tumours, in cases with recurrence, and in bitches. Without castration, tumour recurrence is common. For the large tumours, performing a castration and waiting for the size of tumour to decrease over several months can provide an easier and safer tumour resection. Small tumours frequently regress after surgery, or do not progress. Radiation therapy for adenomas is effective but is primarily used for stud dogs. When there are recurrences despite castration, a second biopsy to rule out a carcinoma is strongly recommended. Cryosurgery can be performed in cases where the size of the tumour is between 1-2 cm in diameter. With castration ± tumour removal, the prognosis for perianal adenomas is good and recurrence rates are < 10%.

Carcinomas of the perianal glands do not respond to castration alone, and a wide surgical resection is indicated. In inoperable or only marginally resectable cases, primary or adjuvant radiation of the tumour site and the sub lumbar lymph nodes is recommended. Another option of treatment is using oestrogen to cause tumour regression, but bone marrow suppression is a significant in risk.

How our cases compared to the literature

Diagnostics

Fortunately, Tob's clinical signs were very typical of a perianal gland adenoma, which was confirmed by the first cytology result and the post-operative biopsy. He had not received a digital rectal exam when first presented to the WVS Rescue and Rehabilitation Centre. If he had, and a carcinoma was suspected, Tob would have received thoracic radiography and caudal abdominal ultrasonography. Tob also did not receive a blood test to determine his serum calcium level to detect hypercalcemia and rule-in/out an anal sac gland tumour.

Treatment

Tob had two perianal adenomas; one at the periphery of right anal sac, which was removed, and another one at base of his tail (dorsal part), which was seen when shaving for the surgical removal of the first mass. The veterinary surgeon decided to leave the mass at the tail base with a plan to monitor its size and characteristics over the next several months, and may plan for resection in the future. The methods used were suitable for this case, according to the literature recommendations for small and nonulcerated perianal gland tumours in sexually intact males. In addition, since Tob was castrated much later in his life, long-term monitoring by his caretaker is recommended due to the risk of development of further perianal adenoma or carcinoma in the future.

The surgical technique in this case is suitable for a perianal gland adenoma only since the carcinoma form would have required wide surgical margins, and also removal of local lymph nodes plus radiation and/or chemotherapy. The literature suggests removal of perianal gland adenomas only if the mass is ulcerated or bleeding. In this case, however, even once the inflammation and infection of Tob's mass had resolved, he still showed signs of discomfort in that area, prompting the vets to decide to surgically remove the mass.

References

- Kahn, C.M., Line, S., & Aiello, S.E. (Eds.). (2005). Integumentary System. The Merck Veterinary Manual Ninth Edition (pp. 772 and 773). Merck & Co., Inc. Whitehouse Station, N.J., U.S.A.

- Kessler, M. (2014). Perianal Tumors. World Small Animal Veterinary Association World Congress Proceedings.

https://www.vin.com/apputil/content/defaultadv1.aspx?pId=12886&catId=57122&id=7054772

[Accessed 27 September 2021]

About the author

Dr Malisa Santavakul (aka "Lukpla") has been working with WVS Thailand since April 2019, after graduating from Kasetsart University in Bangkok and working in the Raptor Centre.

She regularly mentors students (Thai and international) and she looks after rescue cases, both surgically and medically.

© WVS Academy 2026 - All rights reserved.